JOHN J SCHUMACHER

Many thank you to John, Schumacher for giving me access to his documents ans his history and have responded to my questions.

|

IN MEMORIAM |

|

It's with great sadness that I must inform you of the death of John Schumacher. He passed away on December 25, 2016. We should never forget that this man has done for us. Rest in Peace John thank you so much for our friendship. I'll miss you very much. God Bless you! |

<- John in 40's.

<- John in 40's.

And

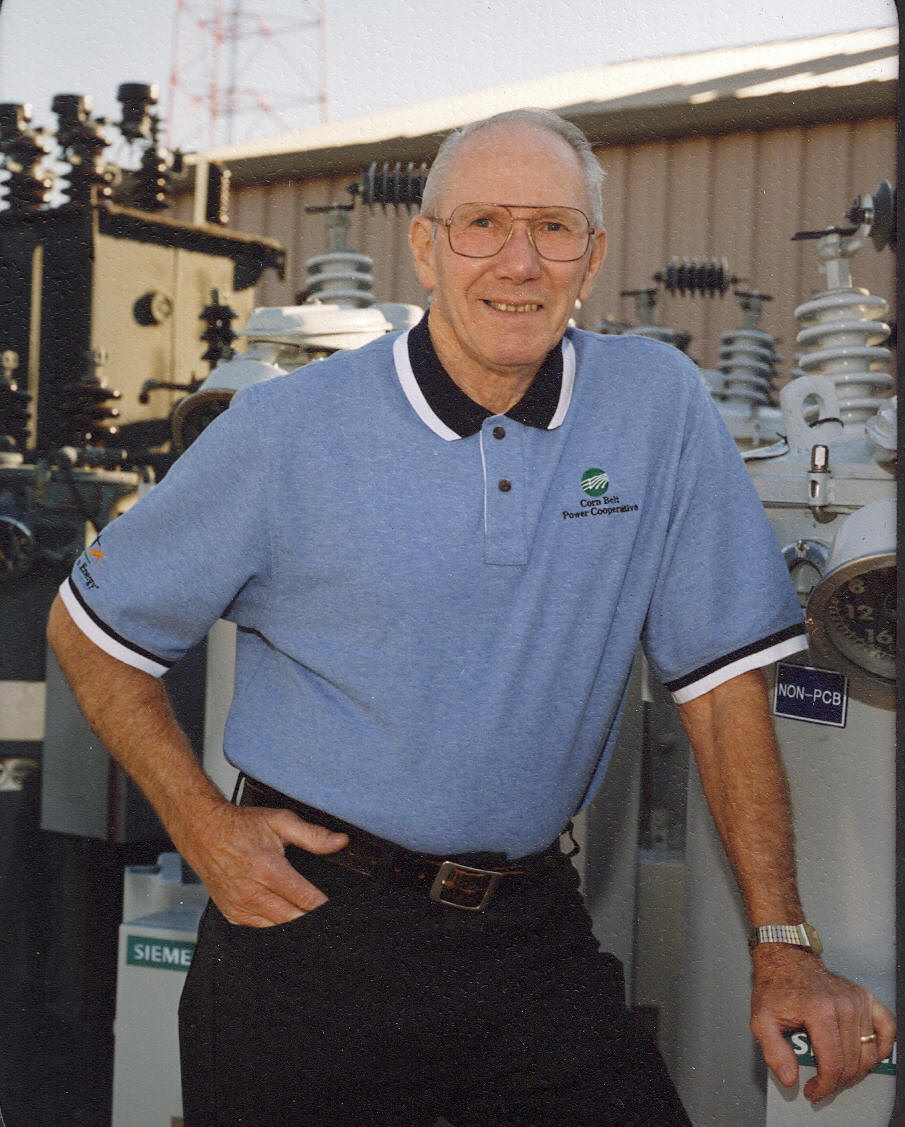

Today ->

John J Schumacher was born in 28 March 1945 in Coons Rapids, Iowa. His parents, John and Frieda Schumacher was a Germans immigrants.

“My Father was born in Rotenberg, Wurttemberg Germany. (His given name Johann, hence John) He immigrated to America in 1898. My Mother was born in Michelbach, Oringen, Germany. (Her given name Friederike, hence Frieda.) She immigrated to America in 1905. ”

His parents were farmers, they had their farm in 1915. Despite the Great Depression and the difficult times, John and his family had never hungry.

“My parents were hard working and conservative so we survived quite well. My two brothers were quite a bit older than I, by 14 yrs and 16 years so I grew up more or less by myself. I love music and have a strong mechanical aptitude so I always had something to do.”

John graduated from high school in spring 1943. Then he helped his parents in farm work. From December 1943, the process of incorporation into the army begins.

“I tried to enlist in the Air Corps but they told me I had a problem with color perception, you know like picking something out of a mess of colors and lines.”

On January 27, 1944, trip by bus from Carroll, Iowa, to Camp Blanding Florida.

“Arrived at Camp Blanding, near Stark, Florida, and it sure looked bleak. The first morning I was awakened by the sound of army trucks going by and I was dreaming that a cattle truck was pulling into the driveway at home and I had overslept. I jumped out of bed with a start and realized, it was Florida, not Iowa.”

“The next day, processing, shots, and placement, etc. There came my next break. We were waiting in line to be assigned to a unit, was called, "Schumacher desk C". The clerk looked up and said Hi John, how are you? At the placement desk was Louie (Louis) Krenmyre, who l knew well, formerly of Coon Rapids, son of a former Methodist Minister. He married Dorothy Thomas, Wesley's sister. I don't know if Louie saw my papers and picked them out or whether it was just a coincidence but it was good fortune nevertheless. Louie said, "We have to get you out of that rifle company, didn't you play an instrument in band? I said "yes, a trumpet". He said, "Good, we'll put in the bugle company, that's a headquarters company, and you will get involved in communications, etc., lots better". So-o-o my second break. It really was a lot better. I went to see a couple of the Coon Rapids fellows down at Rifle Company, and these poor guys were really getting the shaft. We had a good cadre (training non-coms), and good cooks; also quite a few professionals - many musicians. The age spread was mostly in two ranges, mid 30's and right out of high school. We were assigned to huts alphabetically and as you might guess ended up with guys named Schroeder, Schlicher, Schulte and, of course, Schumacher. What a bunch of Krauts! Turned out to be really great guys.”

“Basic training otherwise was pretty much BASIC and we did the usual close order drills, rifle nomenclature, rifle range - I qualified as an Expert Rifleman, (the highest award), on the Ml rifle and Sharpshooter on the Ml carbine - just missed by a couple points. I think l still have the old score card in my "junk" somewhere. We had some communications classes and learned Morse code - kinda. Gas mask drills and infiltration courses were not that much fun, but sure kept us alert. Never did like bullets whizzing over my head, but at least it was just an exercise. It seemed as though we spent a lot of time in the woods and swamps, learning to find our way by compass. There were a few alligators arid snakes but neither one understood compasses so they weren't much help, mostly just got in the way and irritated us and we didn't need any additional irritation as the mosquitoes did an adequate job without assistance. About the bugles, we didn't do a lot with them, other than an occasional practice, and the drum and bugle corps. That was sort a fun since it gave us something to march to other than the non-coms yelling at us. All in all, I guess basic training doesn't seem so bad now, but it does occur to me that loss of memory could be responsible for part of that present frame of mind. Our last bivouac I shall never forget. It was a 20 mile march out, and although it was hot and miserable it was fairly routine and uneventful, as least until after we had returned to camp. Then we were told that we hadn't properly policed the area and that we would be walking back to the area on Saturday, our day off, police the area and walk back the same day. All of the rest of the Regiment was to line up in formation in the parade area and we were to march by on our way to the bivouac site. Anyone in the observing formation who laughed or made any remark would join the march. Needless to say the observers were mighty solemn. Come to find out, some wild hogs had rummaged through the area and dug up some cans we had buried, apparently not deep enough a painful lesson for a real bunch of sad-sacks.”

This first part of his drive ended at the end of May and 6 June 1944, he was back home.

“We were on way home via delay-in-route for a week or so, maybe two. We were afraid that D-Day might do us out of that time at home but it didn't and l got to see my "Special Lady" and family and friends.”

“The next leg was to Camp Shanks N.Y., for another processing for overseas. We did have a day or two to ourselves, and a group went into the City, making the best of the situation. We went to R.C.A. Music Hall and saw the Rockettes, rode the Staten Island Ferry, went to the top of the Empire State Building and had my first filet mignon, at the Roosevelt Hotel, at the recommendation of Army Buddy Sawyer. Sawyer had played in one of the popular dance bands in the area, which I can't remember at the moment, (just remembered- It was Freddie Martin) -but he "knew his way around" and was good to us Kids. We also had a young Jewish boy; I thought he was nearly 7 feet tall, who played percussion with the Boston Philharmonic. His last name was Spector and we called him Hector Spector. No offence intended, and he was good natured about it.”

“After processing again, this time by a clerk named Bastein, that l had made friends with, a real nice guy, who looked at my M.O.S., and said l think we should change your M.O.S. to truck driver. That may have had some influence later on and may have been another one of those little breaks. Then came time to move to the P.O.E. (Port of Embarkation) pier, to board ship the Queen Elizabeth, no less. What an enormous vessel. When we started up the gangplank it seemed to just go on and on, l thought it would never end. The pier was lit up like a Christmas tree and the place was loaded with MP’s. I guess they were afraid somebody might try to run away. It may have been good reasoning at that as there were a few that really didn't want to go. I tried to see how long the ship was and it was huge beyond imagination carrying 15,000 troops. The Queens crossed the ocean alone since no other ships could keep up for an escort, so speed was the protection along with a constant zig-zag course to out maneuver any enemy ship or sub. I was lucky again to get a bunk on one of the main decks, in a converted stateroom. I think there 8 of us in that little room, hardly room to turn around. I had a top bunk - I always got a top bunk if I could so I didn't have someone climbing over me all the time and l always felt a little safer just in case someone got sick. Also, I think they usually let me have it because I had such long legs and could climb easier. I used to like to go out on the bow and watch the sea, and the flying fish and porpoises, but don't remember having much company. Maybe most of the guys were seasick, but I don't remember having much trouble, and as I recall the food was pretty good. We were told that one has a better chance of not getting sick if you eat something and eat regularly. I did. I also recall being impressed with the beauty and splendor of the ship, which was apparent even as converted to a troop carrier. The large entertainment halls had been converted into chow halls but the ornate décor was still evident. I think it took 6 days to cross and we dropped anchor in a bay off Gurrock, Scotland, then were shuttled to shore by ferry or barge or some things called lighters, and we were impressed again by the size of the Queen out in the bay as we looked back at her. Then we loaded aboard those little Scottish or British or whatever, trains with the little engines that go, "boop boop" or "wheep wheep" when they whistle. The countryside looked a lot like some of the travel films we now see on TV. Part of the trip was at night and we didn't see much, but travelling through the English countryside by train was about what you would expect, back yards, gardens, bombed out buildings and old people. I guess all of the young were in the service.

Arrived at Chisleton, young recruits were given to new vaccines. John came in what was called a Repl Depl is a camp where new recruits were placed before final placement. It was during this period that John was the "knowledge" with the German V1:

“One of the nights I remember because it was so clear and the stars so beautiful. Searchlights probed the sky for enemy planes, and I heard my first German Buzz-bomb. The English said, it's O.K. Yank, if you hear

them you are O.K. It's the on you don't hear that gets you, the same as with artillery shells, but we never overcame the panic that accompanied the whistle or swish of one going over, or landing in front of you, not knowing where the next one was going to land.”

Shortly after, John Schumacher was assigned to the 17th Airborne Division.

“My assignment was to the 194th Glider Infantry Regiment, Headquarters Co. 1st Battalion. A heavy weapons company, 81mm mortars and heavy 30 cal. Machine guns. I was in a mortar platoon. We were issued new clothes and equipment as the airborne units were outfitted differently than conventional ground troops, lighter to facilitate faster movement. Our rifle was a .30 Cal. folding stock carbine, which we carried in a canvas scabbard at our side when it wasn't carried on a sling. When we carried full gear I don't see how it could have been any lighter, maybe heavier, since I think we carried everything we owned with us. This is the unit where I made some of my best friends including combat buddy John A. DiLuccio. Dukes family is of Italian ancestry and was from Pennsylvania. Another stroke of good fortune was my association with this good friend. I actually think he was looking after me. He was married and had one child, maybe two, I can't remember for sure. We would go to Swindon to a movie, buy knickknacks and shoe polish and on one occasion had our pictures taken. (boy did we buy a lot of shoe polish as we were expected to look sharp at all times, and the boots were the first to show). We had weekend passes to London and Bristol where we could stay at the U.S.O. and sleep between clean, cool white sheets. Gosh, did they feel nice. On one trip to London we had the opportunity to visit Westminster Abbey and went to church service there on Sunday morning. It was not crowded. We also had a short tour of some of the London landmarks of historical significance.”

Despite the anxiety he perceived in the announcement of this new assignment (it

was not voluntary), John was proud to belong to this elite unit.

A few days before Christmas, the division was placed on alert. The Germans had

launched their offensive in the Belgian Ardennes.

“On Christmas Eve we moved to the airfield but everything was fogged in, as it also was on the continent wich was a major cause of the problems there, since there was no air support for the troops in the Bulge area around Bastogne. We were served Christmas dinner at the airstrip and slept in tents that night. The next day, Decembre 26, the sky cleared and we loaded into C47s and flew to a beat up runaway near Rheims, France where spread out all over the place for safety, until the 6X6s came and picked us up. The Germans apparently had a habit of strafing areas with sizeable troop movement. I remember a particular incident on that truck ride because we had “C” rations during the trip to the Belgian border. The “C” rations were bad enough to start with, but one of the truck drivers decided to try to warms his on the manifold of his truck engine. Well, it got too hot and exploded – what a smell! I’ll bet that poor guy spent many hours cleaning that engine compartment.

“We were dropped off at a tiny little French village named Beaumont, near the Belgian border, where we took shelter in some bombed out buildings without any roof and then it snowed all night, but at least it kept us out of the wind.”

“We didn’t know what was going on at the front at that time, but every night about dusk a Kraut recon plane would go over, flying real low – we called him Bed-check Charlie. He was no doubt checking out troop movement and strenght. Also in the town was a small contingency of French Maquis. Theses were remnants of the Free French that our I&R was working with. Theses poor guys didn’t have much to work with on their own, but they seemed to make the best of it and were a real thorn in the German side. They also had a very short life span if they were captured, as the krauts just lined them up and executed them. Our next move was into Belgium and the Bulge area toward Bastogne, and so frenzied it denies recall, other than individual incidents. As we moved up we passed burned out trucks, tanks, artillery pieces and all sorts of other destroyed equipment, buildings and dead bodies. This was our first clue that we maybe in for a rough time. We were attached to Pattons Third Army and deployed near Houmont, Flamierge and Bastogne. Patton said we should be in sufficient sternght so we shouldn’t meet much resistance and there shouldn’t be any armor to sontend with. He was wrong, as Headquarters Co’s first enemy contact with German Tanks, we thought Tigers and they really poured it to us. The roar of that first round from a German 88 is beyond description, a sobering experience, especially when you’re scared to death to start with. We couldn’t tell where the fire was coming from, but that first round took out our antitank gun just a hundred yards to the right of where our squad was holed up in some shell holes. The platoon Sergeant kept calling for a bazooka man but couldn’t find him. Other than the bazooka we didn’t have anything else to fight tanks with. This left us all in a state of momentary shock, after this baptisme of fire. Then the tank withdrew. A typical German maneuver was counter attack and withdraw. Then our armor moved up and the battle subsided for a time. It was during this melee that Colonel Pierce came upon some of the heavy weapons platoon and asked where the rifle company was, and why we, heavy mortars, were up on the line. We moved back a couple hundred yards and dug in at the edge of the some woods. This is where Duke and John J made use of some of our engineering skills and dug the class “A” foxhole, a double (2 men) with built in C ration, candle and sterno can shelves and anti-tree burst cover leaving just enough room to crawl in and out. Periodically we were harassed by shell fire wich many were tree bursts, thus the need for a cover. This area is where most of us ended up with some frost bite from those miserable shoepacs. This is also where the chow truck pulled up to bring us a hot meal, our first in some time, and while we were in the chow line the Heinies dropped in a couple mortar shells. One of the guys had his mess kit full in one hand and a canteen cup full of coffee in the other, and when he heard the shell made a dive head first into a nearby foxhole, never spilling a drop of anything. To add to the wonder of it all, there was already a guy in the hole, a laughable outcome to a not so funny situation. Luckily no one was hit this time. I don’t remember whet happened to the guy in the bottom of the hole.”

“After few days we started to advance – on foot – mostly through knee deep snow, sometimes by road or trail always on the lookout formines which were mostly in the roads. Some of the snow had developed a thick crust of ice which would hold us up occasionally, but then we would break through, making for very difficult walking, carrying our gear. We were fortunate most of the time to find a barn or shed to sleep in and it was a treat to find a barn with hay to sleep on. This old farm boy could get a good rest in a hay loft, most of which were attached directly to living quarters. Guard duty at night was cold, fearful and lonely. The weather remained extremely cold and the stress soon began to take its toll.

Our diet of mostly K rations probably didn’t enhance our physical and/or mental positions either, but when you are hungry almost anything tastes good.

“One incident that I vividly see in my mind to this day occurred when we were advancing in the area near St. Vith. We came upon a building, maybe a home or shop that was the victim of a lot of artillery and small arms fire with holes everywhere in the walls and roof, plaster and debris all over the floor, and there in all of the rubble lay a Crucifix undamaged by all this. I picked it up and carried it thru the rest of the war. I offered, on a couple occasions, to give it to one of my Catholic buddies but was always told, "No you keep it". Anyway I still have it. I recently was sharing the story of this incident with Monsignor Francis Sampson, an Airborne Chaplain, with whom we became good friends and who, after the war, was appointed Chaplain General of the U.S. Army. Monsignor said, "John you did the right thing by keeping it. It couldn't mean as much to anyone else as it did to you.”

“After a couple forced night marches we moved back to Luxembourg city for a couple days R & R. We slept on the marble floors of Luxembourg Hospital. I think it was a hospital, (heard recently that it was a girls school) but even the marble felt good; at least we weren't freezing. Then back to the front again, moving up to the Our River where we dug in. It was on this last overland move that we stopped for a break in a farmyard or Villa with some stone buildings with tile roofs. General Patton rolled up in his jeep to check out the situation and proceeded to get stuck in the snow. I was called to help push the Jeep out and I have a picture of the incident that was shown in the TALON brochure that was printed about the 17th, after the Bulge. I am sure the Germans were watching Patton for we were immediately under shell fire. Patton yelled, "You men take cover" and took off cross-country. The shelling stopped.”

“The Our River was our last stand in the Ardennes and that is where I got my eardrum popped when I didn't duck quite quick enough from the muzzle of our mortar while we were shelling enemy emplacements on the other side of the river. My ear felt real hot on the inside and sure did ring! I never did report the incident since I thought that if I was too dumb to duck it was my own fault.”

“By this time it had started to warm up a bit and then things got to smelling pretty bad - death became very apparent as we came upon to a lot of German dead that were caught in the blizzard and couldn't get picked up. Also a lot of dead animals that were not priority on the disposal list. I think the hardest thing was seeing blood, in the snow and finding the frozen bodies of some of our own, - enough said on that. The wet snow made it difficult to get around and we did a lot of Jeep pushing for a while. From the Our River we moved to an ancient little Belgian village where most of us came down with flu or some kind of crud that required masses of paragoric to control, such vile tasting stuff. In a couple more days the weather moderated some more and after a few days of recovery we were treated to a concert from an army band. This was play time for a few of the guys who had a couple captured German machine guns and ammo; and they took them to a bill outside of town and tried them out. Finally we were delivered our duffle bags with some clean clothes. Thus ended the Bulge and Ardennes campaign for the 194th and we loaded onto trucks and moved back to France to Chalons Sur Marne. This turned out to be the reorganization and training area for the Airborne drop into Germany. This reorganization involved the disbanding of the 193rd GIR, since both the 193rd and 194th were both decimated during that conflict. A third battalion was then added to the 194th, forming the new 194th Combat Team. The 17th AB as a whole, had in excess of 50% casualties in the Bulge and Ardennes, according to membership roster. (Membership rosters included all personnel, backup, clerical, supply, etc., so losses of line troops were devastating, much higher than the percentages indicated).”

John was sent to the "D" Company of the 194th GIR, while the regiment was stationed at Chalons sur Marne.

“At Chalons Sur Marne came another of my good fortunes, or at least I thought so. My Friend, Duke, was driving a jeep for one of the officers at the time, and he told me one day that the "Old Man" needed another driver and that he, Duke, told him he knew a farm boy that could drive anything, so the Colonel sent word for me to report to the motor pool and drive him around for the day. This was my first try with a jeep, but I guess I did O.K., since I got a call to report to the motor pool again and was assigned a jeep. The rest of our preparation time was consumed with weapons drills, training flights, getting equipment ready and I even ended up trying to teach some of the city drivers how to back 2 trailers hooked together. It's similar to backing a very short coupled 4 wheeled wagon, only harder. German propaganda radio kept asking us when we were coming to Wesel to see them." They were no doubt aware that an Airborne operation was imminent somewhere. The continual propaganda appeared on the surface to be a ploy to trick to trick our intelligence, but in the end turned out to be factual. They apparently knew more than we thought. »

Throughout this period, Axis Sally, the German radio voice for the GIs were sending messages to the Golden Talon.

“The German propaganda radio message kept asking us when we arrived at Wesel to meet them. They were probably aware that an airborne operation was imminent somewhere. The constant propaganda was simply a way to try to counter our intelligence service, but in the end, proved realistic. Apparently, they knew more than we thought.”

On March 21, 1945, the 194th GIR was sent to a staging area near an airfield. It had to prepare for D-Day. In this area, John received during the docking technique for well hang his jeep in the glider and avoided as it does the imbalance.

“March 23 was consumed with orientation sessions, map study, checking eguipment and ammunition, rest and relaxation if that was possible under the circumstances, and eating. Part of the orientation sessions took place around a sand table, the purpose being to present as realistic a view of the landing areas as possible. Our sand table orientation was presented by a young PFC with a definite German accent. About 46 years later I met this young PFC again in Ft. Dodge, Iowa, now Dr. Herb Jonas a veterinarian and friend of our own Dr. Richard Shirbroun, a friendship that developed when Dr. Jonas son and Dr. Shirbroun's son Randy were in veterinary school in Ames, Iowa at the same time.”

24 March, it’s the day…

“That night was short and not too restful. On March 24 we were up at 3:30 A.M. and had steak for breakfast. We wondered if that was indication of a last meal, but I guess the cooks meant, "So long fellows and good luck". I think too that the steak is supposed to stick to the ribs and possibly cause less nausea on a rough flight.”

“Anyway we all took our dramamine, a wise move. While still dark we moved to the runways for final loading. Tow planes for the CQ4As were all C47s, double tow, in other words 2 gliders behind each tow plane. Tow ropes were from 300 to 500 feet in length, and were said to have contained enough nylon to make 1500 pairs of ladies nylons.”

“Each tow had one long rope and one shorter in order to avoid glider collisions. There were a few cases where the shorter towed glider got tangled in the longer tow, but I think there were only three such mishaps in the entire Varsity operation, a credit to the Glider pilots.”

“Readied for takeoff the C47 s were all lined up head to tail on the runway with the gliders on each side of the runway beside their respective tows.

Towropes were all laid out neatly in an S pattern to avoid getting tangled. Takeoff was scheduled to begin at 0800 hrs. "H" Hour, or landing time, was 1015 hrs, with all tow planes being warmed up well in advance of take off, no place for stalling here. It seemed like we were in the air within 15 minutes and circling for position in the flight pattern when all planes were in the air. The takeoffs were nearly flawless, which was not much short of a miracle considering that the glider loads as well as the planeloads were all in excess of rated payload. In addition to an additional trooper in the passenger seat of my jeep we carried a full load of ammunition. Our companion glider in the double tow carried my trailer also loaded with ammunition and supplies, both volatile cargoes if hit by AA. Hopefully the pilots would cut loose together and bring both down relatively close together, but no guarantees.”

“At the signal for takeoff the two planes went to full throttle and when the flagman dropped the flag the flight crew released the brakes under full power. When the slack went out of the towrope there was a momentary strong tug until the stretch was gone and then we snapped ahead like a rubber band with all of the stretch gone. The short towed glider took off first then the longer tow (gliders pull easier when airborne), and then the tow plane, which was by then most of the way to the end of the runway. The ride was extra rough due to all of the turbulence created by the masses of aircraft in the sky, and as I already said, these birds are rough riding at best. The extra turbulence created a lot of extra stress on the pilots and it was necessary for them to share the controls every fifteen minutes due to the difficulty in maintaining control.”

“The view from a glider in the air amounted to practically nothing, especially from the seat of a Jeep. There were small 8 or 10-inch portholes from which the view was less than poor, and you could see somewhat through the nose section straight ahead. This view was mostly of other planes and gliders in the sky train, until we approached the Rhine, then smoke, flak and burning planes. The pilots had difficulty identifying landmarks due to the smoke, partly from tires on the ground, partly from British smoke generators they used to obscure their ground movement, and from heavy smoke and flak from German Anti-aircraft batteries located within the LZ and DZs. Our pilots were able to locate our LZ, when they hollered, "This is it guys, we're going down", and pulled the trip on the towrope. This was the first time we could see the ground, and the small fields lined with hedgerows, dots of smoke and AA tire, other gliders already 'on the ground, but no Rommels asparagus (posts set in the ground to tear the gliders apart). They took us down fast and we landed hard, taking out one wire fence but avoiding any other obstacles. We stopped fairly close to a road, about 100 yards from an AA gun, got out fast, propped up the tail with a 2x4 (standard equipment and procedure) and unloaded the Jeep post haste. The next job was to find the other glider with my trailer. There was still a lot of ground fire in the area so we moved with a great deal of caution until we could figure out where it originated. We found the other unit in an open field about 300 yards away, right in the middle of a swamp. This was also an open area and still the subject of enemy fire if they saw anyone moving in the area. Another concern was to be alert for additional incoming gliders since they were silent in their approach after being cut loose from the tow plane. It didn't look like we could get to it with the Jeep, so we went in search of a dropped towrope to use so we could pull the trailer from the road. We found a rope shortly and rounded up some more help to extricate the trailer successfully without anyone getting shot.”

Shortly after the glider is to rest, drivers helped John and his friend to extract the jeep unit. Then the two slipped away to join the pilot group of soldiers trained rally driver. Before leaving, they abandoned their heavy body armor to the ground.

“They left they took off their jackets, pitched them and hollered, "so long guys, good luck". My passenger and I thought that since we were riding, a little extra protection wouldn't hurt so we cabbaged onto the flak jackets and put them on. We were to rendezvous with Lt. Anderson at a courtyard on the other side of the canal, so we set out to find him which we did shortly. When he saw us with the flak jackets he looked at me and said, "What are you doing with those damn things, they are no good, give it to me", which I did. He threw the jacket on the ground, pulled out his 45 Automatic and shot a hole right in the middle and said, "see what did I tell you". Ironically he was shot a couple weeks later on the road to Munster, in the forehead, through his steel helmet, by a German sniper. He was a good officer and we missed him.”

Another image will remain forever marked in the spirit of John:

“That afternoon sky was still full of planes, mostly cargo, dropping supplies by parachute, and as I watched, a B24 type came in low at 200 or 300 feet above ground, and the airman pushing out the bundles became entangled in the lines and was jerked out along with the cargo. I can still see him falling through the air as if he were grasping for something to hang onto, a picture forever ingrained in my mind.”

John Schumacher spent his first night on the German’s ground under artillery fire, which British bombed German lines. Then the days following, the 17th Airborne broke the German lines and went to the north and the great city of Muenster.

“The Krauts were still pretty though at times and never stopped counterattacking. On one weird occasion, when we were moving down, or up, a road cleaning up “hot spots” when the kraut started dropping mortar shell around us , and I slammed on the brakes of the jeep, everyone bailed out and jumped in the ditch. I either didn’t get the emergency brake set tight or kicked it when I bailed out and the jeep started to roll Whitey Heitsman saw it before I did and jumped up and reset the brake. At one of our 17th Airborne reunion, 3 or four couples were sitting around a table reminiscing about some of these dumb things that happened and one of the wives said “i don’t know hw you guys ever won a war!” I think we wondered sometimes ourselves! Another time we were getting a little ahead of our supply lines and were getting low on fuel. We captured a German supply depot with a supply of synthetic gasoline. They could make anything synthetic it seemed. We found what was claimed to be ersatz butter made from coal. Anyway we loaded some of the gasoline onto our fuel racks just in case we ran out, but we really didn’t know how it would work in our engines, so just kept it in case of emergency. The stuff did burn though, just like regular gasoline so we were fairly sure it would work if needed We also ran onto a distillery some where along the way where they made Doppelkorn. This, I presume was kind of corn whiskey, not being an expert on this, that is only a guess. A couple of the guys decided to try some, much too much in fact, and they went out of their head, which was really not that unusual for them. This batch must have been “green”... It was reported that one of the guys spilled some on his shoelaces and the next day the shoelaces fell off. I swear it to be the thruth. At this same location we liberated a German motorcycle, which turned out to have a non-functioning clutch, so some of us entertained ourselves for a time with the challenge to ride the thing clutchless. It didn’t take much to entertain us. Then back to the war!”

After Munster, the John’s regiment went to Duisburg, Mulheim, Essen ... During this advance, he remembers the news by the arrest of Franz von Papen, former German Chancellor and his son, an officer in the SS in their hunting property by members of his section.

“Another occurrence happened while advancing down a road, apparently close to enemy lines judging from the sound of gunfire. We stopped at a country crossroad where the powers-to-be were trying to decide what to do. After the loss of Lt. Anderson we had a couple acting CO’s, and I think acting probably is more appropriate than we would like to believe. On this occasion we had as our fearless leader an arrogant young jackass impressed with his own importance, (no disrespect for his rank intended), who looked at the map, pulled out his compass, no fooling, and said: “We go that way.”

So away we went, down the road, fat dumb and happy. Suddenly everyone screeched to a halt, jumped out of our vehicles and started yelling: “Hendi Ho, Hendi Ho” (that is supposed to mean Hands Up, or something like that in German). Where were we? Right in the middle of a German heavy weapons (81mm mortars) platoon, in the process of digging in, and who I’m sure, thought they were 1000 yards behind the lines. The element of surprise left little time or alternative for them. I think they must have been ready to surrender anyway as they all immediately started toward us with their hands up. Our next problem was a German machine gun squad just over the hill behind the trees, and we needed to make a hasty departure before they became aware of our presence, so we turned back toward whence we came with a “whole bunch” of prisoners. I think the little jackass (sorry) thought he did something great when he turned over the prisoners. Another incident of a little more humorous nature occurred on this same advance. Again we were moving down the road in convoy, meeting little resistance at the time, when we overtook a British convoy with some armoured vehicles. We stopped and asked one of the “Tommies” if we were running into some resistance, (by the way, this was approximately 3:00 PM). The Tommy just looked at us very serious and said: “Oh no, we just stopped for a spot of tea”. What a characters, but maybe this kind of reasoning is what helped them endure the war for so long. General Ridgeway has told us once that once we get rolling, and if we should overtake the British columns, just keep moving and go on by. General Ridgway was XVIII Airborne Corps Commander and there was no such word as wait in his vocabulary, but there was no need for waiting here and we were soon rolling again toward Duisburg, while the Germans were surrendering so fast that we just took their weapons, told them to put their hands over their heads, and pointed them to the rear to find their own way.”

“One of the hairiest experiences was an all night advance, during a heavy rainstorm. Night advances were always difficult as we couldn’t use lights lest we give away our position. We had only the small cats eyes, small lighted slits that you could only see probably up to 100 ft away, under good conditions, by which to identify other vehicles. As you can imagine they were almost impossible to see in the rain, and our windshield wipers were hand operated, to make it even more difficult. I had to keep my front seat passenger awake to work the wipers, as I had my hands full watching and driving. Is was a miracle we didn’t run into each other, but then we weren’t moving very fast, and were kept very alert.”

“Somewhere along the way we came upon a concentration camp, mostly Poles we thought, poor starved shadows of humanity. It looked like the Germans just took off when we moved in. The people hade to have medical treatment, and deloused first thing. Along with the filth and squalor of the concentration camp were found mass graves, bodies dumped in trenches and partially covered up. When we reached Duisburg, our forces gathered up a group of Germans I perceived to be a local leaders, Nazi sympathizers etc;, and made them dig up the bodies, put them in coffins and bury them in the town square. I have a couple pictures, the quality not too good, of thet occasion taken at the burial site right across the street from the Duisburger Hof. Feelings were still running very high regarding the treatment of the detained persons that survived the horrible nightmare. I have no idea what eventually happened to these poor souls, but suspect they were to be repatriated ine way or another.”

John with his jeep in Duisburg, Germany 1945.

“One the first night in Duisburg we were assigned beds wherever they could be found, until we were placed in permanent quarters, that is permanent on a temporary basis. Some of the Platoon, me included, were placed in the Duisburger Hof, or Hotel. The beds had satin sheets and what seemed like down quilts or covers. I have never before or since, slept on such luxurious bedding. After that it was back to reality again.”

“In the early days of occupation when I wasn’t occupied at the motor pool, I was occasionally assigned to a squad led by a Sgt. Kreuzer who spoke fluent German. Our job was to go out and pick up Nazi officers and leaders who had escaped capture during the Allied takeover. I guess we thought we were sort of a macho squad, as we would go to the addresses where the suspects were thought to be hiding, block all the exists and bust in before they had a chance to get away again. There were two occasions that stick in my mind. One was on the 6th or 7th floor of an apartment building where we were looking for an ex SS officer. We raced up the stairs and into his apartment where we found him sitting at a table eating, and when he saw us and was identified as the person we were looking for, just stood up and walked out with us without another word. Another time we had a tip that someone was hiding in a wine cellar. We went there in the usual manner and found about dozen people, not the least of which was a mouthy old woman who rattled on and ridiculed us for coming in there with our guns and acting so bg. I suspect she thought we didn’t understand a word she said because she seemed to be addressing her remarks to the other people, not us, but we didn’t care a heck of a lot. It turned out there was no one there thet we were looking for so we left.”

“Not all of our time was consumed with drudgery and on occasion we were able to come up with our own entertainment. Several of us who were driving had located some old-fashioned bulb horns, and fastened them on the sides of our jeeps. We would drive quietly down the street, or even coast a little if we could find a down grade, and we would slip up along side a group of girls and give the horn a blast. It always got a reaction, and that certainly couldn’t be classified as fraternization – could-it?”

“In July, good fortune struck again and I was notified that I had been drawn for a 3-day pass to the French Riviera. We were loaded into a C47, and flown to Nice. I don’t remember a lot about the flight to Nice other than it took several hours, it seemed, and it wasn’t the smoothest ride I have had. We just had the wooden bench seats on each side of the plane and I don’t think there were any pads, but can’t swear to that. I know we flew over a lot of mountains, the Alps and others. I don’t recall any of us having any lack of confidence in the old C47 Workhorses ability to get us to our destination. They had a reputation for dependability that stands to this day. Right after we landed another C47 came in right behind us and blew a tire on landing but the old girl just wobbled a little and the pilot pulled off to the side of the runway without a hitch. I don’t remember this as a particularly scenic flight either, as we had our backs to the windows and it was not too comfortable looking out for any length of time. The ride from the airport (landing strip), was by truck – our ground transportation was always by truck if I wasn’t driving myself – to our Hotel, the Imperator, quite a nice Hotel and just a couple blocks from the beach. There wasn’t a whole lot to do but an occasional movie, but the food was good, the scenery and beach interesting. The stories about the French girls changing into their bathing suits on the beach have been highly exaggerated. A couple tours were arranged for us, one to a perfume factory at Cannes and also a tour of the ancient architecture in the area, not super exciting, but interesting and a welcome change. When we returned to Duisburg it was to be only a few week until we were alerted to get ready for our return to the States in preparation for deployment to the Pacific, which would very likely have resulted in the participation in an airborne landing on the mainland of Japan.”

“From Duisburg, we were split up, some of the guys going to the 82nd Airborne and on to Berlin with the occupation forces. The rest of us were to be reassigned to the 13th Airborne to return to the States for deployment to the Pacific as previously mentioned. We went first to Luneville, France to await shipping orders. I was kept fairly busy at the motor pool, driving a 3/4 Tons weapons carrier to Nancy about once a week to pick up a couple kegs of dark French beer, pretty poor stuff. While we were at Luneville I had an opportunity to pack up some souvenirs to send home, including the mauser, pistols, bayonets, etc… which made it home in good condition. I had also packed a couple first class German Officers parade swords, which never made it. There was a guy in Supply that handled them for me and I know he stole them and sent them home for himself. I had him pegged as a crook from the first time I met him. He cheated at cards, always won at craps and had a truly underworld type of personality. I know he did it!

While at Luneville I was able to find out where the 82nd A/B was and got a pass to visit High School classmate Larry Raygor, who had participated in the Airborne operation into Holland and was also in the Bulge Campaign in Belgium It was good to see him again, not too much the worse for wear, and pretty much the same old “Toots”. He moved on to Berlin with the occupation contingent.”

On 12 August 1945, John embarked with his companions on board to the USS Thomas Berry at Cherbourg harbor, France. After 8 days of crossings, the ship arrived in New York where men could see the Statue of Liberty. At that time, the war with Japan was over, the Japanese had surrendered after the atomic bombings.

“Those of us assigned to the 13th A/B went to Fort Bragg, North Carolina, and had our own way most of the time. The rest of the time in the States was pretty much a lark, and for us “Combat Vets” our assignments were mostly to keep the “Kids” on their toes, and scare the pants off of them with war stories. While at Fort Bragg, I ran on to Steve Garst, another home town kid, who was in Quartermasters and who brought us ice cream on Sundays. It is nice to have friends in the right places.”

Finally, January 29, 1946, John Schumacher was discharged. He returned to his

parents' farm, he married Wanda February 14, 1946.

He did not return to school, but followed a

government-sponsored program called "Institutional Training Farm was" that would

help veterans re-learn the agricultural practices.

“My parents were ready to retire so they moved to town and Wanda and I stayed on

the farm. It was only a small farm and eventually proved inadequate to provide

a sufficient income for a young family. During the next 20 years we built up a

modern Dairy herd and sold Grade “A” milk which was bottled and sold for human

consumption. As I said this did not provide enough income so I joined with

2 friends in the feed and farm fertilizer business for 5 years. Then another

friend asked me to join with him in the Real Estate and Insurance business which

I did for fourteen years. Then I formed my own Real Estate and Insurance Firm

which I operated with Wanda’s help until 2005, at which time I finally retired

at age 80. It was also about this time that the health of both Wanda and I

began to deteriorate.”

His wife Wanda passed away in 2010 after a long sick; As John said, despite some

financial difficulties at some point, they had a very happy life during their 64

years of marriage. They had 3 son and now they have 3 grandchildren, son and a

daughter.

Since the end of the war, John Schumacher never returned

to Europe.

“I have always dreamed of returning some day to revisit the combat areas and of course would like to visit where my parents were born in Germany. They immigrated in 1897 and 1902. My youngest son Jeff has indicated he would go with me and his wife Melinda said, “Can I go too?” They have travelled in Europe so it would be great to have them along. Jeff is very interested and supportive of my military past.”

Among his decorations, John Schumacher received the Bronze Star for his participation in Operation Varsity, 40 years to the day after.

“I was still proud to receive it.”

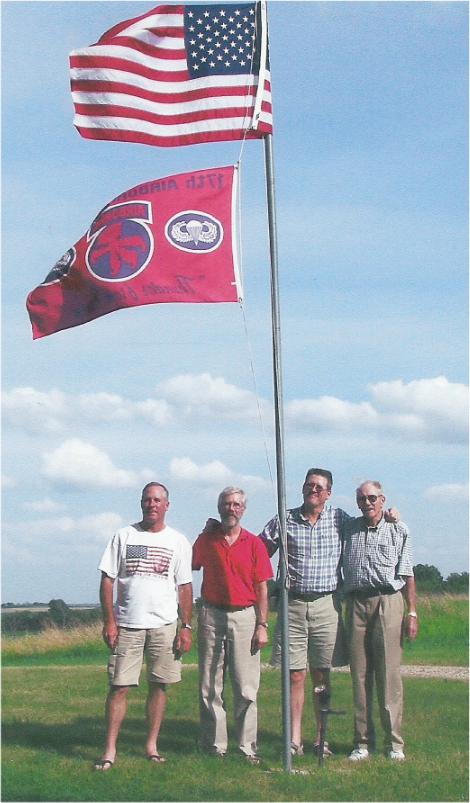

<=

John / &

his boys

=>

<=

John / &

his boys

=>

John, his wife Wanda and his family (sons, grand-sons and daughter-in-law)