Murray F Moorhatch

Murray F Moorhatch

|

IN MEMORIAM |

|

I only publish now the story of Murray simply because it was not over yet. And unfortunately, it never will. Sadly I learned about Murray Moorhatch’s death. He passed away on February 27, 2010. Here is his last message: “This is my final farewell! I've made my last jump into the cosmos--No longer above this earth, I'm free of pain flying with the Eagles.” If you come here... Please, Stop... 5 minutes... Think about this man... He was a great man! |

Murray

F Moorhatch was born in Highland Park, Michigan on September 29, 1923.

"I had a very happy childhood. "

Guided by a desire to serve his

country, he left school at the end of his 3rd year to join the army on February

10, 1941. He

was only 17 years old. He

cheated on his birth certificate to pretend he was 18 years old.

He joined the 210th Coast Artillery in

Detroit, Michigan.

He attended a basic military training at

Fort Sheridan, Illinois.

However, he was soon tired of walking and shooting, he wanted to fight.

A little bit later, he received a leave and got

back home. He

met a friend who was recruited by the Canadian army. He

was preparing to be sent overseas to fight. Murray

Moorhatch did not think twice, he moved to some other armed forces.

“I Joined up because ther was a war going on.

This was before Pearl Harbor, and I was afraid it would end before. I got in the

action. So I went Absent Without Leave (AWOL) to London, Ontario and enlisted

the next day. I didn’t tell anyone, not even my folks. I was in the 4th

Canadian Armored Division and two weeks later shipped to Quebec City.”

Murray Moorhatch travelled in various cities before arriving in London in

February 1943. Because

of his qualities and his knowledge of typewritring, Murray was appointed as a

clerk.But

Murray was bored in the office. He

did not want the war going on with him sat behind a typewriter. Having

obtained a leave, Murray Moorhatch went first to the U.S. embassy and a U.S.

recruiting office to leave the Canadian Army but in vain.

When

Murray met an American MP, he presented himself as a deserter and asked the MP

to arrest him.

The MP escorted him to his unit to be brought to

a young lieutenant. Murray

explained the situation. He

could leave the MP making sure he would soon hear from the U.S. Army.

“I went back to the Canadians and by this time I was AWOL from them. So the Company Sergeant Major put me on report and took me in front of the Colonel.”

He

was received by a Colonel and was given permission to speak to him privately. Murray

explained the situation. The

Colonel shook his head and confined him to the barracks. A

little bit later, Murray was discharged from service in the Canadian Army. He

returned to the U.S. Army.

There, he

received a new uniform and a place to sleep with the hope to fight soon.But

once again typing led him to work in an office in the Adjutant General's Office

in

London.

“I was working in General Eisenhowers HQ in London, England in 1943 and I didn't want to be a soldier who sat at a desk. So I volunteered to enter the Airborne Infantry. I received my airborne wings November, 1943.”

Murray Moorhatch, unhappy, totally hopeless received an

"advertising" for the airborne troops. He was sure the

fight was guaranteed. He wrote to the recruiting

center, was summoned and, after passing a medical examination, was ordered to go

to Auburn, England where was parked the 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 101st

Airborne.

The two weeks training consisted in gym and walking. Once, he packed 5

parachutes for his first jump. On the Saturday of the second week, Murray went

on the 5 jumps and on the Sunday, he received his wings and his diploma from

famous Captain Herbert Sobel’s hands (former CO of Easy Company). Once His

training was over, he joined D Company 2nd Battalion 506th PIR.

“That was the biggest thrill of my life. When I left London everybody was saying I’d never make it because I was skinny and didn’t have muscles. On my first pass, I went back to the office and proudly flaunted my wings in front of every last one of them!”

|

|

Murray photographed in Hyde Park, London, 1944 |

During the night of June 5, 1944, Murray could not just do

better than to drag himself to his C-47 that was taken him as he was loaded.

He really wanted to get to. The last days, they had assimilated as much

information as possible, played poker and ate the "last meal" consisting of ice

cream.

Inside, Murray was praying for this night to be the right one. Not like the

previous day as it was canceled. He almost thought it was a joke when an officer

boarded on the plane and announced that Operation Overlord was delayed and when

everyone was down. That was at this very moment Murray appreciated the famous

policy of the army: "Hurry up and wait! "

In addition to his parachute, his gun and all his equipment, Murray received a

special little system of communication to identify the friend from the enemy. This

small object was called a "cricket". A "click" had to meet two "clicks".

“The crickets really were brilliant because the Germans wouldn’t be able to distinguish us as Americans. We all thought it was very clever.”

The aircraft began to roll down the runway just after midnight. Murray felt the aircraft leaving the ground, he knew there would be no turning back. From then he was 90 minutes away from the reason he trained so hard. He did not know what to do or how to do it so he sat quietly with the rest of his comrades.

“It was so quiet, no singing like we usually did. I remembered how I had volunteered because I wanted to be in the shooting war. It would have been so easy to stay where it was safe. But I could have never lived with that. I had no fear of what was coming. I was committed to going out the door of that airplane. We all were.”

The flight over the Channel was uneventful until a thick fog

shrouded the coast and the Normandy drop zones.

A few minutes later, Murray was surprised by the first

shot of anti-aircraft batteries of the enemy. During

the next 20 minutes, he looked anxiously towards the outside while the flying

C-47 tried to avoid the flak fire.

Suddenly, the Jump Master shouted: "Stand Up! Hook up! "

Murray and his friends stood up and carefully checked the equipment of the

parachutist in front of each other.

Murray cannot remember seeing the green light indicating that he could

jump. Second on the stick, he put his hands on the outside of the plane and

jumped off.

Diving in the dark night, he could not see a bloody thing, not even his

parachute which was supposed to make him land safely. But he knew that he was

open as he was drifting slowly in the cool air.

As he did not know the height he jumped from, Murray was waiting for

landing. Within a few minutes, he could see the earth without being able to see

properly the type of ground on which he was about to land.

Once on the ground, Murray grabbed his parachute and took it off. He was alive,

but very lonely.

“That moment was eerie. It tightened up all my 'sensors' real quick. I thought about my mission; where I am, what I’m supposed to be doing. I checked what I had left; some things had been sucked away into the night. Then I put one foot in front of the other and started up a path I found.”

Hearing someone close to him, Murray took his cricket, his

best friend at this very moment, and clicked.

From his two clicks another click replied and then appeared a guy from the 101st

Airborne. After discussing their situation, the two men decided to walk south

and to try to locate their unit.

Some kilometers away, the paratroopers came upon a group of paratroopers of the

82nd Airborne who were already fighting against the Germans on the side of La

Fičre bridge.

It was a small structure, but one of the most important objectives of D-Day as

it was only one of two places where the tanks could cross the Merderet and could

prevent the Germans from crossing the river and could counter-attack Utah Beach.

The action Murray wished for so long would become one of the bloodiest battles

of the war.

“Those were the longest three days and nights of my life and

that was just the beginning. All I remember is pounding gunfire going back and

forth and back and forth.”

Once everything was over, Murray felt a huge

pride in the spectacular victory of the intensive training he had followed.

Then, towards Ste Mere Eglise, he met a lot of

Americans forces.

“And I couldn’t help but feel those we had lost were alongside as well.”

Arriving at Ste Mere Eglise, Murray asked to return to his

unit, nearby Utah Beach. Arriving at his unit, Dog

Company, his commander asked, "Where the hell were you? "

After telling his adventures with the members of his unit, he joined along his

unit in other battles to the west until late June. The beaches were safe and the

Germans were moving back.

Murray was back to England in July. The fighting had changed him a lot. He was

then a man.

Murray Moorhatch also participated to Operation Market Garden in Holland, he

jumped over around Eindhoven and fought a few months in the area of "the

island".

But the fightings in the Belgian Ardennes during the Battle of the Bulge would

change his personnal and professional life.

During summer 1944, Murray Moorhatch made a request to the army to marry his

girlfriend. Around 6 months later, he got the leave, his fiancee was waiting for

him in Paris. Murray Moorhatch left the army for a leave in the French capital,

we were on December 16, 1944.

They got married in an American church on the Champs Elysees. The newlyweds

spent their wedding night, but on the next morning, on December 18th,

Murray received a phone call ordering him to rejoin his unit as soon as

possible. The newlyweds could not know the tragic situation taking place in the

Ardennes.

Arriving in Bastogne, Murray Moorhatch met loads of GIs who were moving back,

the blank stare, like zombies.

“They look so disheartened. You’d try and talk to them and get no response”

The paratroopers were desperately short of ammunition and

equipment for the winter. They took what they could on the GIs who were

retreating.

On 21st of December, the Germans had completely surrounded Bastogne. In

the afternoon of December 22nd, Murray learned General McAuliffe's

response to the German demand for surrender: "NUTS!

“Nobody had thought of giving up. Every Soldier in the 101st thought he was the best in the world. So we loved that answer. We decided then and there McAuliffe must have “Big Ones”. That one four letter word lifted our spirits and morale and kept us going.”

Moorhatch Murray, and many others of his comrades spent

Christmas in a foxhole, trying to warm up. On December 28, Murray Moohatch was

helping to dig a foxhole when a German artillery barrage began.

A shrapnel hit him in the leg. The

doctors put a bandage to stop the bleeding. He remained on the front line two

more days before being evacuated to a hospital.

The war was over for the young soldier who wanted to

fight.

Those years in the Army were the best of his life. It is this period that made

him a better man.

“As a teenager I was a little flighty; Iwasn’t a good student. I’d goof off it I could. The Army created a man out of a teenager. It’s the kind of experience that teaches you to enjoy your life. ”

Murray Moorhatch also speaks about the comradeship in the army between the soldiers. Close links that are not found anywhere else. Moorhatch Murray was discharged from the army with the rank of Sergeant.

“I never had the need, opportunity or even the privilege giving my life up for somebody else, but I would have gladly done it.”

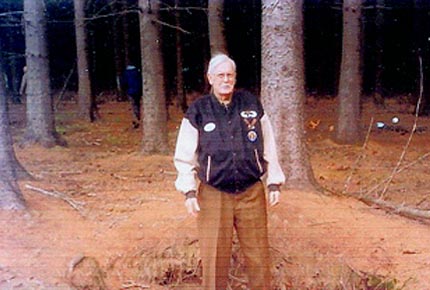

Murray Moorhatch back in the Ardennes forest.

60 years later, here he is

standing in a foxhole in Bois Jacques.

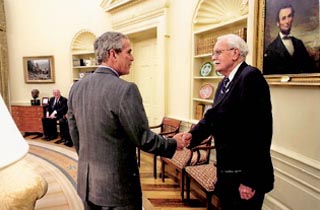

Murray was received by President Bush at the White House in the Oval Room.

Murray Moorhatch during his last trip to Normandy. August 2008.