Richard "Dick" Manning

|

IN MEMORIAM |

|

It is with great sadness that I must announce the death of my friend Dick Manning. He passed away 20th May 2013. Dick, thank you for your friendship. Rest in Peace. Thank you so much for what you did for us. I will never forget you! God Bless You! |

Many than you to Dick for taking the time to answer my questions. For me spent his time. And also for the documents he sent me.

<=

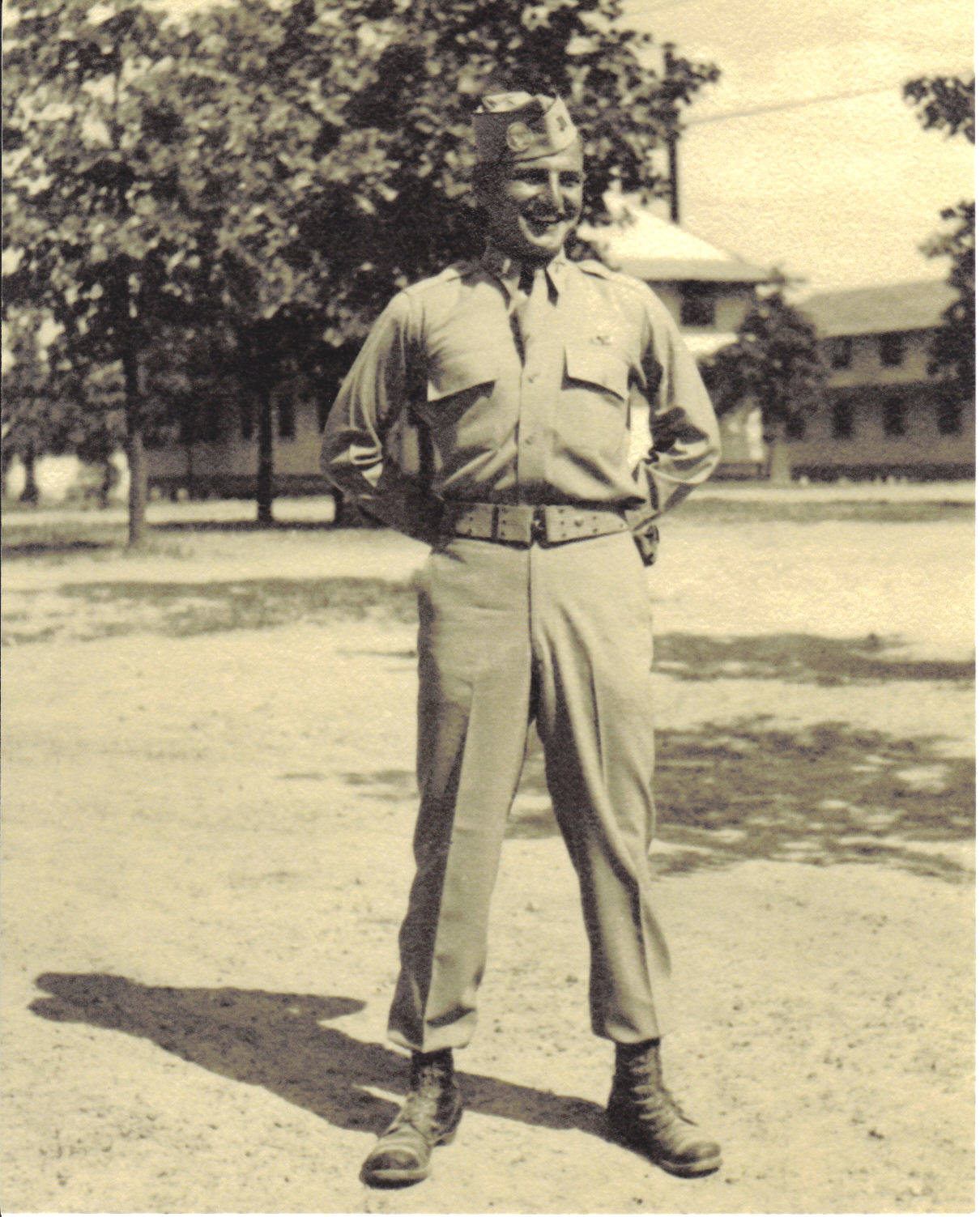

“Dick” Manning in 1944

<=

“Dick” Manning in 1944

Et "Today" =>

Richard "Dick" Manning was born on September 2, 1924 in North Carolina. His father, John H Manning is a military career.

“My father was enlisted as a Private in the North Carolina National Guard in 1913. In April 1914, he had been promoted to the rank of Captain and sometime thereafter his unit served on the Mexican border in General "Black Jack” Pershing's U.S. Army expedition into Mexico.”

“Just back in February 1917, his unit left for the front in Europe in May 1918. My father's unit was reorganized as part of the 119th Infantry Regiment, 30th Infantry Division. After training, the 30th Division was, in May 1918, moved to France where it became part of the AEF again under General Pershing."

<= John H Manning

His father participated in the Somme offensive. He was later promoted to Major and commanded a battalion during the Battle of Le Selle in Ypres, St. Mihiel and Meuse - Argonne.

“In my youth, I met and came to know General John Van B. Metts, who had been my father's Regimental Commander in the 119th Infantry in the War, as his home was across the street from the home of my Grandparents.”

After the Armistice in November 1918, then Major Manning accepted the

opportunity offered him to remain in the AEF Headquarters in Paris. While in

Paris, he was summoned as a Liaison Officer to lead the Under Secretary of the

Navy, Franklin Delano Roosevelt and his wife Elinor, during three days of the

battlefields in France and Belgium. Elinor Roosevelt recounted that tour in one

of her books.

Major Manning returned to North Carolina in July 1919 and remained with the 30th

Division which was deactivated from Federal service and reverted to its National

Guard role in North Carolina and Tennessee. Later that year he became a

Lieutenant Colonel in the 120th Infantry Regiment of that division.

It is in this military setting that was born Richard "Dick" Manning. It was

therefore natural that he embraces a military career.

“By the time I was around nine years old, I began to stay much longer at the Guard's summer encampment at Camp Glen near Morehead, NC, along with the sons of other National Guardsmen. From 1933 to 1938, I was trained along with the other young boys in any number of military matters, including the use of several military weapons, with most of which I was familiar from my previous stays at Camp Glen. Before my eleventh birthday, I had qualified as an expert rifleman with the Army's standard infantry weapon, the1903 Springfield bolt action rifle, which was an excellent weapon, but which had quite a kick! A year later I qualified as an expert machine gunner with a Browning water-cooled machine gun. Also, we practiced all sorts of military actions along with the Guardsmen, and we were treated almost as men, not little boys. The more I learned on those encampments, the less attractive my lead solders became.”

At the end of every summer encampment, as a grand finale, there was a full dress parade during which the troops marched by the reviewing stand where the then Regimental Commander, Colonel Don Scott, a long time friend of my father, and my father as the Second in Command, were on the stand, saluting the men as they passed to the marching music of John Philip Sousa. The last group to pass the reviewing stand consisted of the small boys, sons of the Guard members, dressed up in uniforms, all of whom saluted those grand figures on the reviewing stand!

“I loved every moment of my times at Camp Glenn, and of course my ambition was to become a soldier like my father.”

“Then came September 29-30, 1938, and the Munich Conference, when Neville

Chamberlain, along with the French and the Italians handed over to Hitler the

Sudentenland on the German border. Chamberlain then returned to England and made

his infamous speech promising "Peace in our Time." Then came the March 1939,

occupation of Prague, and then the take-over of the entire democratic Czech

Republic.

Probably because of all those events, in August 1939, the National Guard did not

go to Camp Glen, but rather, went on maneuvers in the swamps of Louisiana near

the Red River on the western border near Texas. As always, I went along, and I

realized that the exercise was pretty close to "the real thing."

On September 1st, 1939, the eve of my 15th birthday, and only eleven months after Neville Chamberlain's "Peace for our Time" speech, German Panzer Divisions commenced the massive invasion of Poland. Immediately after the invasion of Poland, to their everlasting glory, England and France declared war against Germany. World War II had begun.”

“Then, toward the end of April of 1940, at the dinner table, my father, who was then a full Colonel and the Commanding Officer of the 120th Infantry, told us that we must prepare for his being away for an extended period. He said that even though the enabling legislation had not yet been introduced into Congress, the National Guard was going to be called into active Federal service on September 16, little more than four months away. He said the call-up would be for only one year, but he believed that he would be away much longer than that.”

“Without saying a word to my parents, I decided that I did not to be left behind by my father. If a war was coming, I wanted to be in it! Even though I was only 15 years old, I made up my mind to go with my father into the Service.”

“The next day, I went to the National Guard Armory, and there met with Captain John Allen, the Company Commander of the local National Guard Company, who had known me as long as I could remember. He and my father had served together during and since the War, and they were close friends. I told Captain Allen that I was there to join the National Guard. Openly surprised, he asked me how old I was, even though he knew I was only 15, as well as I did. I said I was 18, and gave him a birth date of April 22, 1922, which I had calculated before I got there. Captain Allen then went to another office. When he returned, he said, "OK Soldier, let's sign you up!" I filled out the forms and I was sworn in and then I saluted him. I was in the National Guard.”

“I was later to learn that when Captain Allen left the room he telephoned my father, and told him I was there seeking admission to the National Guard, and asked what he should do, as I he knew that I was not old enough to enlist. My father said, "How old did he say he was?" Allen responded, "He says he's 18." My father quickly responded, "Well, by Golly, he's 18, sign him up!”

“That night at the dinner table he said to me, very seriously, "Son, you gave

your word today to your Country that you were 18. You must never go back on your

word, so you just had your 18th birthday." I very quickly answered, "Colonel,

you didn't have to tell me that; I know what I did and will stick by it."

“A few days later, Captain Allen called me and said that there had been some

error in the paperwork about my enlistment in the Guard, so I had a chance to

back out, as I was not officially enlisted. Without mentioning a thing to my

parents, I told him I would be there to get things straightened out, and I went

back to the Armory, and redid the paperwork, and they got it right the second

time, so my official enlistment date was not in April 1940, but in May. But I

was committed from the moment Captain Allen first said I was in, and I never

looked back!”

Richard Manning (right) and his father (left)in Fort Jackson, South Carolina.

“First, More about WWI, as I told you, my father took then Under Sec. of the Navy, FDR and his wife on the three day tour of the battlefields. Years later, under different circumstances, then President Roosevelt, was to recall that tour to my father.”

“At some point in the summer of 1941, at Ft. Jackson, when I was still a private, we were told that there was to be a Review of all the units on the entire Post by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. That, of course, was a very big deal, and meant that all equipment, buildings and soldiers had to be brought into perfect condition for the President who was our Commander in Chief.”

“The day of the President's arrival, the Company was ordered out for yet another inspection early in the morning, and everything was found to be in order. The units were then marched one by one to positions along the main road through Fort Jackson. There were tens of thousands of GIs lining the road, all in formation, about an hour or two before the President was scheduled to arrive. In front of the entire 120th Infantry Regiment stood my father, the Regimental Commander.”

“The day of the President's arrival, the Company was ordered out for yet another inspection early in the morning, and everything was found to be in order. The units were then marched one by one to positions along the main road through Fort Jackson. There were tens of thousands of GIs lining the road, all in formation, about an hour or two before the President was scheduled to arrive. In front of the entire 120th Infantry Regiment stood my father, the Regimental Commander.” During the President's review of the troops, made in an open touring car, he made two unannounced stops at random before two of the Regimental Commanders, one of whom happened to be my father. When the President’s car came to a halt in from of him, my father stepped forward and saluted the President. My father was then introduced to President Roosevelt by the Post Commander, a General who was riding in the car with the President. We could see that some words were being exchanged which we could not hear, and the President started laughing. My father later told me that the exchange went something like this: “Mr. President, this is Colonel John Hall Manning, Commanding Officer of the 120th Infantry Regiment.” The President responded, “Oh, I remember Colonel Manning very well, I knew him when he was a major and the staff cars in France could not go less than 60 miles an hour.” That was when President Roosevelt began to laugh. My father explained to me that they had made the tour in an open Staff Car, which my father frequently drove rather fast, and on one occasion a near accident had caused the car to make a 360 degree spin on the road, after which they had continued uninjured. Clearly the President had never forgotten that tour with my father.”

“Fast forward to March, 1943, when I was in the Parachute School at Ft. Benning, the following occurred:

We were next introduced to the parachute tower, which was 250 feet high, and had

been used at Coney Island for tourists dropping in parachutes attached to a wire

on the top, with guide wires running down the sides of the chute to the ground

to make certain the chute dropped slowly and straight down so that no one could

be injured. I have read that the same safety devices were in use on a tower at

the Parachute School, but I have no recollection of ever having seen such a

device at the School. My recollection is that there was only one tower, with

four arms from which parachutes with men hanging from them could be dropped in a

free fall, with no safety devices.

On the day I was to make my first drop from the tower, there was much activity

going on at the Post. Everything was being cleaned up or painted, giving every

indication that something big was in the offing. As usual, the troops on the

Post were not told what it was about.”

“The day of the President's arrival, the Company was ordered out for yet another

inspection early in the morning, and everything was found to be in order. The

units were then marched one by one to positions along the main road through Fort

Jackson. There were tens of thousands of GIs lining the road, all in formation,

about an hour or two before the President was scheduled to arrive. In front of

the entire 120th Infantry Regiment stood my father, the Regimental Commander.”

As the time approached for my ascent up the tower’s arm, the wind had increased

to about 30 mph, which would normally have resulted in cancellation of the drop

as being too dangerous. Not that day, however. I was pulled up to the end of the

tower arm, and then nothing happened. Normally one was released within a few

seconds of reaching the tower arm, but I just hung there, twisting in the wind,

wondering what was going on and when I was to be released. I was somewhat

concerned that the high wind might blow me into the tower which could cause the

chute to collapse, but then, I had been taught how to maneuver the chute by

pulling on the risers, the two woven fabric bands that ran from the chute pack

to the shroud lines holding the chute itself.”

“As all of that was passing through my

mind, an open touring car appeared below, coming toward the tower area with many

motorcycles preceding it and several cars behind it. As the car came very close

to the tower area, I could not believe my eyes - there was Franklin D.

Roosevelt, the President of the United States and the Commander in Chief of the

Army, right below me. And at that moment, there was a bounce and I was swinging

below the chute in the strong wind, tugging the risers to keep me off the tower.

I landed on the sawdust standing upright, and managed to collapse the chute

before the wind took it off dragging me behind it, and when I looked around for

the President, he and his entourage had departed, but that was an exhilarating

experience, to have made my first tower drop for none other than the President!

My father had driven the President and Mrs. Roosevelt on a tour of the

battlefield of France, and then, years later, he had been re-introduced to the

President at Fort Jackson, and now I had parachuted from the big tower for the

President.”

Now back to Ft. Jackson, in 1942

« Dick » Manning was transferred to a rifle company from the Service Company shortly after Pearl Harbor.

“After I had been in the rifle platoon for about three months, my father was transferred out of the Regiment, being replaced by a Regular Army Colonel, a graduate of the Military Academy at West Point. The same fate befell all of the other Regimental Commanders, as well as the entire 30th Division General Staff. All were replaced by Regular Army graduates of West Point, regardless of their comparative qualifications, As I was to learn much later, that was part of a scheme to put Regular Army West Point officers in all National Guard command positions, so they could gain the command experience necessary to further their careers. It mattered not one whit to the powers in the Regular Army that many of the National Guard Commanders were far more qualified in many ways than those who replaced them. My father had served in the Mexican Border campaign and in severe combat in WWI as a battalion commander, and he was certainly more qualified to lead the 120th Infantry into battle than was his un-battle tested replacement. Moreover, it was my father who had assisted in the rebuilding of the 30th Division after WWI, and had trained his men, and trained them well, for the many years until the Federal Government required their services. That was indeed some repayment for a long time loyal officer, who gave a large part of his life to the National Guard, because he knew its value to the defense of his Country. Those indefensible actions were attacked in a book, entitled “The Rape of the 30th Division.” by Major General Henry D. Russell, the 30th Division Commander (brother of then Senator Richard B. Russell of Georgia), who was removed and replaced by Regular Army Major General William Simpson at the same time as my father was replaced.”

“Later, in 1944, when my father was the senior officer on an Army Reclassification Board in Italy, which was charged with finding some place for officers who had been relieved of their commands for failing to perform their assignments as required, the Colonel who had replaced my father was sent to the Board; he had not made the grade!”

After his father’s departure, Dick was promoted to Corporal. His Platoon Leader told him that the promotion would have come earlier, but his father had not wanted it, as he wanted me to spend more time as a private in the rifle unit before being promoted.

“Around May or June 1942, even though I was only seventeen, and still not old enough to legally enter the Army, I decided that I was going to try to gain admission to the Infantry Officer Candidate School, known as OCS, at Ft. Benning, Ga. I wanted to arrange matters such that if I was accepted into OCS, I would not graduate until after I had reached 18. If I was going to become an officer, I thought I should at least be old enough to be legally in the Army.

I had to pass a number of tests, the last being an oral test before a number of

senior officers none of whom I had ever seen before, and I must have passed the

tests, because In July, 1942, I was told by my Company Commander that I would

leave Ft. Jackson for Ft. Benning and the Infantry OCS early in August.

That was my last connection to Old Hickory!”

Richard Manning then went home where he joined the paratroopers after becoming an officer of Company E, 2nd Battalion, 513th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 17th Airborne Division and finally in 1944 he was promoted to 1st Lieutenant.

This photo was taken at the end of a movie that Dick turned to the need for a documentary on the drive.

After a parachute jump, the men installed a machine gun.

eft to the right: Lt. Fagan, Platoon Leader of the 2nd Platoon, E Company (KIA January 5 or 6, 1945)

- Lt. Manning (WIA January 5, 1945) and Pvt. Russell Herriford (WIA January 45)

From late 1943 to May 1944, Dick Manning commanded the first platoon. But he was

demoted as assistant platoon leader of the 81mm mortar section by Lt.Col. Miller

for incompatibility of temper.

On August 20, 1944, after a period of maneuver in Tennessee, the 17th Airborne

Division left the U.S. for England. She was stationed at Camp Chisledon.

On December 16, 1944, the Germans launched their counter-offensive in the

Ardennes. The 17th Airborne was sent into the line between 23 and 25 December

1944.

On January 3, 1945 the 17th Airborne Division was sent to the front. The next

day, the 513th PIR will have its baptism of fire.

His battalion is positioned Mande St. Etienne in the southeast of Flamierge.

The attack is launched, Company E attack towards the summit of the hill,

supported by artillery fire. The Paratroopers are moving in an open landscape

covered with snow.

Fifteen minutes after the assault, 1st Lt. John W. Deam made contact with "Ace"

Miller to say that he takes the hill. His men have finally reached the enemy

foxholes which constitute the starting line. However, the woods on the left

flank, is fiercely defended by the Germans, despite the barrage, and when

Company F approaching within 100 meters of the forest, the advance bogged

down. Artillery batteries continue to save the paratroopers of the total

massacre.

The platoon leader, 1st Lt. Ivan the Stoshitch, was hit while his deputy, 2nd

Lt. Charles Puckett leads the men in the woods. At this moment, they are taken

by shooting on their backs and can not move. The artillery shells the right

flank, where five or six men are able to enter. But the 1st Lt. Samuel Calhoun

is affected, and the few remaining men are grounded. The platoon is at the

center will never reach the forest.

Miller watches the scene from his headquarters, located just 150 meters from the

fighting. It monitors the situation hopeless.

He immediately called the 1st Lt. Dick Manning, whose platoon is kept back.

The pack of Richard Manning, who was stationed in the south-east of Mande St.

Etienne, is not under enemy fire.

“He ordered me to the Battalion observation post on the north side of Mandy. I hurriedly went up there - about a half a mile - and saw what was happening to F Co. in front of the woods and E and D Companies on the right, all under very heavy fire from the woods; well men were lying in the snow all over the fields, dead and dying.”

“Col. Miller told me to send a patrol in and I almost blew up.”

I told him I would do it my way and walked out. I had not seen or talked to Lt. Deam that morning. I went back to the CP to tell Lt. Deam what I planned to do, and I had my messenger get my Assistant Platoon Leader and two sergeants to meet with me so I could tell them all at the same time.

We met behind the company CP which is the large rock building on the east side of the road just before where the road branches to Champs.

I just started talking to them when sniper with a automatic weapon fired and hit the three of them who were so close I could touch them.

Lt. Deam was killed instantly and the other two were seriously wounded. I was not hit although all of the bullets had to pass my head to hit them. And then got the men of the Platoon together and we crawled in the snow, bayonets fixed, across the field on the immediate west side of the finger and jumped up and into the woods and then cleared the whole woods and about 30 to 50 minutes. And that attack which was about 28 men and we had two men wounded none killed.”

For this feat of arms, the 1st Lt. Richard Manning will be decorated with the

Distinguished Service Cross.

Richard will receive his decoration than two years

after the war.

“Colonel Miller wrote the citation on Jan 4. I have the original written in pencil; General Miley saved it for me and gave it to me at a 17th AB reunion in Cherry Hill, NJ in the early 1980s”

“When I first came to in the deep snow, my left foot was behind my shoulder. I was in and out of consciousness for some time; then some of the men straightened my leg and put me in a slit trench (after removing its dead occupant). I was then much later put on a stretcher, carried to the road about 100 yards away, and put on a rack on the top of a jeep. As we started down the hill an artillery barrage came in almost on top of us, and the driver and his assistant jumped in the nearby ditch -- for which I did not blame them -- and when the shelling was over, they got back in the jeep and we started down the hill again. Another artillery barrage came in and the same actions were repeated. We finally reached the aid station, a wire brace was put on my leg and the wound to my shoulder was patched up and after a while I was put in an ambulance with three other guys. After stopping at several forward hospitals, which turned us away because they had no room, we finally came to one that would accept us. I was only one remaining alive.”

The brilliant career he had promised to be stopped in its tracks.

"I spent three years in hospitals. My leg was saved, but years later I had

horrible pain.

"

After three years in different hospitals, Dick Manning returns to his home in Raleigh, North Carolina. He joined the University of North Carolina.

“I had gone in the Army at age 15 and never got past the tenth grade in high school.”

During all these years, Dick suffered his leg.

“I was partially crippled with a very bad left leg and knee which got worse as time went on.”

“My leg was almost blown off by a tree burst 88mm shell. The Doctor in England said he would "try to save it" and he did. Unfortunately, it had to be re-fractured and reset some weeks later. Then after 10 months the Drs said it was healed; unfortunately, the left knee was very stiff.”

Richard Manning entered the college in the same time with the rehabilitation. During his rehabilitation exercises, it is advised to cycle to extend his knee. Unfortunately, he re-fractured. His knee never recovered really in place. Until 2009.

“The capillaries in my feet had been badly damaged; last year they began to show signs of gangrene; after several other procedures failed, the leg had to go.”

Dick Manning earned his law degree and had great success as a New York lawyer

specializing in international oil issues.

He was one of several companies including oil and gas drilling in Ohio, for a

chain of service stations in Montreal and a trading company with offices in

London, Rotterdam, Hamburg and Buenos Aires.

“I also handled legal matters in Canada, the Bahamas, England, France, Germany, Belgium, Switzerland, Italy, Nigeria, Bahrain, Dubai and Abu Dhabi, the Philippines, Hong Kong and Japan. Now I live on the top of a mountain in northeast Pennsylvania.”

Dick is married three times first time in 1949 after being demobilized. He had two daughters. Then, in 1956, he married while working as a lawyer for the oil refining company in Puerto Rico. He also had three daughters. Finally, he met his current wife:

“In 1973 met my present wife, Melanie (the love of my life); she came to work for me in my law office in NYC; not long after that we were living together. Married in 1979 and still together.”

Today, Dick lives in a big old house on top of a mountain in Pennsylvania, about

1900 meters with his wife and three dogs Boxers.

Dick still sees his three youngest daughters. It also has 4 girls and 3 little

son.

Today, Richard Manning spends his time surrounded by the love of his wife to

write the story of his struggle to Mande January 4, 1945 but it continues to

meet certain legal issues.

"Dick" Manning with his wife Melanie

Their Beautiful home in Pennsylvania.