Lynn W Aas

Many thank you to Gregory de Cock for the article about Lynn. Thank you Lynn and his family for their kindness.

<-

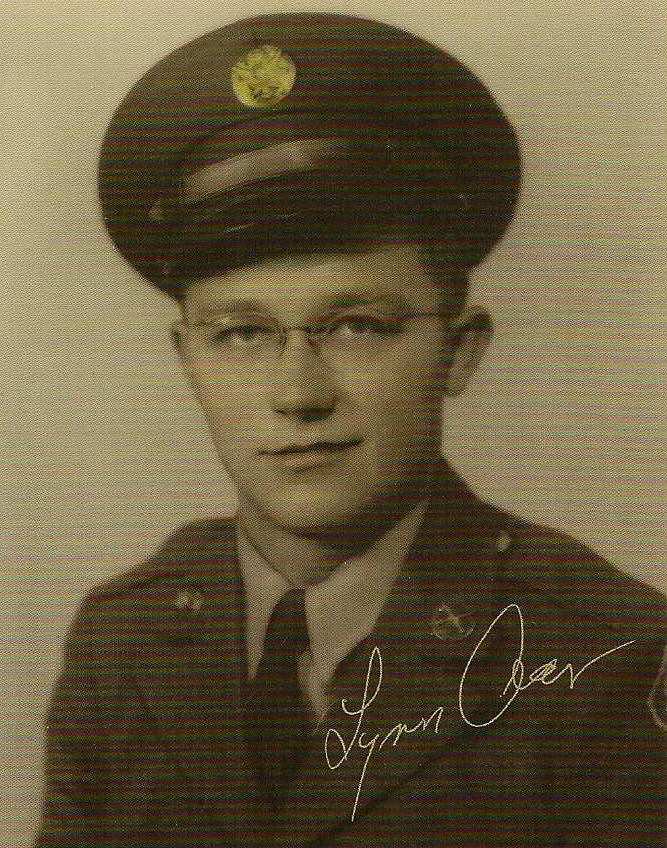

Lynn Aas - 1944

<-

Lynn Aas - 1944

Today ->

Lynn William Aas, son of George Aas and Anna Olson, was born ona 4th of June 1921 in Benedict, McLean County, Noth Dakota. Of Norwegian descent, his four Grand Parent hailed from the Skien, Trondheim and Tromsø area. Third child of the family, he grew up surrounded with his two brothers and three sisters in his father’s farm. The young boy attended the local Primary School while taking an active part in various farm works and cattle care in his spare time. The family was not wealthy and the farm did not make much profit. The Great financial Depression in the early thirties made things worse and Lynn had to miss out an entire school year. In this dull rural area, the young man used to hang out with lots of people, most of them from European backgrounds, Germans, Swedes, Ukrainians and Norwegians of course. As a teenager he attended Velva High School, away from the family home. In 1940, once done with High School, Lynn spent another year at the farm, to make up for the low family financial situation. However, willing to get an education, he joined the University of North Dakota in Grand Forks, in the fall of 1941.

On the path of war :

While studying at the University, Lynn volunteered in the US Army Reserve on August 18th 1942. He was given the ASN 17084245. He was called into the service in March 1943 at Fort Snelling, Minnesota. He went on to receive basic training at Camp Wheeler, Georgia, for a five months period. He passed a psychotechnical test and joined in August the Army Specialized Training Program, a series of specialized and highly technical trainings aimed at qualifying highly specialized military technicians. During a little less than a year, Lynn attended Engineering classes at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology close to Boston, Massachussetts. Lynn was very proud to be a part of this renowned school. Thanks to the ASTP program, Lynn was automatically promoted to Private First Class. The program was called off in February 1944 in order to release personnel to fighting units. With deep regrets, Lynn was automatically transferred in July 1944 to Dog Company, 2bd Battalion, 193rd Glider Infantry Regiment, 17th Airborne Division. The Glider Regiment had been officially created on December 16th 1942, but actually activated on April 15th 1943 at Camp Mackall, North Carolina, in the same time as the division commanded by Major General William M Miley.

Pfc Aas did not go through life camp at Mackall, near Hoffman, North Carolina. The Division had left to take part of the Tennessee Maneuvers and settled at Camp Forrest, close to Tullahoma, Tennessee, on March 27th 1944. He began straight away to undertake the specific training for glider troops, and build team spirit with his new brothers in arms. Long walks calisthenics, field problems and physical fitness were his daily occupations. Even though he joined in late, Lynn had no trouble adjusting to his new job as a foot soldier. He did not get his parachutist wings but eamed the glider badge.

On August 14th, the young man learnt about the upcoming overseas movement and briefly transited at Camp Miles Standish in Taunton, Massachusetts. On August 20th, he boarded a ship in Boston, heading for Liverpool, Great Britain. He reached Camp Chiseldon next to Swindon in Wiltshire, on August 30th, after eight days at sea and two days on a train ride. Men had to set up camp before resuming training and intense day and night maneuvers in the surrounding countryside. In September, the 17th Airborne Division was alerted, as a reserve force for the 82nd and 101st Airborne Division invoided in Operation Market in the Netherlands. The 17th Airborne Division ultimately would not take part. Occasionally, Lynn would go leave and visit London or some touristic area, in order to have some fun.

Prelude to Hell

On December 19th 1944, the 193rd Glider infantry Regiment (193GIR) was informed that it was to transfer urgently to the Belgian Ardennes, to counter a German offensive launched three days earlier. Preparations were hasitly. In the evening of December 21st, 2nd battalion 193rd GIR (2/193GIR), Lt.-Col. Harry Balish commanding, assembled at Membury airfield in Berkshire to board C-47 transport planes. Howaver, bad weather prevented to organize an aerial bridge until December 24th late in the afternoon. Lynn landed on airfield A79 in Purnay, near Reims. The division went under George Patton’s 3rd Army command. After a brief stopover in Camp Mourmelon on Christmas day, 2/193GIR was taken by truck to Boulzicourt, next ti Charleville-Mézières. Pfc. Aas and his battalion stayed in that area until January 1st, setting up roadblocks, guarding the Meuse bridges and patrolling both side of the river, in order to establish a defensive line, should the enemy break through.

Late on New Year’s Day 1945, Lynn boarded a truck bound for Massul, near Neufchateau in Belgium, and then proceeded to Sibret the next day. In the afternoon of January 3rd, 2/193GIR went under 101st Airborne Division command and was called as division reserve in the woods around Isle-le-Pré, south west of Bastogne. Snow was two feet deep, visibility less than 600 yards and temperature dropped to minus 6 Celsius.

On January 4th, as snow kept on falling heavily along with thick fog, the rest of the regiment also went under 101st Airborne Division command and remained in reserve. Around 17.00, trooper Ass reached the woods north west of Villeroux, in support of the 513th Parachute Infantry Regiment (513PIR) first day attack to regain Flamièrge. Lynn remembers arriving near Bastogne : « Previous fighting must have been rough and the ground was littered with American and German bodies, frozen stiff by the cold. Destructions were all around. As we du gour foxholes, Grave Registration personnel picked up the bodies with two trucks, one for our dead, the other one for the Germans. They were all piled up. This way was my first contact with combat trauma. » Starting to realize what laid ahead, Lynn tried to persuade himself that, in order to survive, he would maybe have to kill, one thing he did not think he could do. To toughen up, he used a peculiar method : « I walked towards the body of a tall, young blond German. I thought things over, and started to kick him, to covince myself that I could hurt him. He was my enemy, and this was war. This lifeless faces reminded me of my Ukrainian and German friends I had grown up with. I did not want to kill, but I had to, if I were to survive. »

Around noon on January 5th, 2/193GIR set up camp east of Mande-Saint-Etienne, in two isolated patches of wood. Lynn was to remain there for two days, until that fateful moment to launchan attack against German positions. The first cases of frostbites occurred at this time. On January 6th, the regiment covered the 17th Airborne Division’s right flank, being reunitedto that unit after being released by the 101st Airborne Division, its neighbor to the east. Lynn’s battalion received the order to take the next day all the wooden area east of Flamisoul, at the cross roads from Champs, Mande-Saint-Etienne and Flamisoul.

The Belgian Ardennes, of the end of innocences :

Sunday January 7th 1945 marks the very first day in combat for the 193GIR, a day forever engraved in the memory of Lynn Aas. Snow was knee deep high, temperatures down to minus 6 Celsius and fog limited visibility to 200 yards, depending on the terrain. 1/193GIR took up position south of Flamisoul and 2/193GIR east of Mande-Saint-Etienne. The attack started at 08.15, following an artillery barrage. Under cover of the fog, Lynn and his comrades moved up the Mande-Saint-Etienne to Champs road. In open terrain, they were soon pinned down by machine guns, mortars and artillery fired by the Germans concealed in the woods, the rougher the going. Supporting mortars in the back could not weight on the issue of the battle facing machine guns and 88s. In front of Flamisoul, 1/193GIR faced the same fate and could not even reach its primary objectives. 2/193GIR however succeeded in reaching the woods, in the face of strong enemy resistance.

The situation bogged down to the point that around 16.00, Colonel Stubbs, CO 193GIR, ordered his regiment to retreat. At nightfall, the situation was miserable. 104 and 108. Panzer Grenadier Regiments of the 15. Panzer Division had inflicted the 193GIR 144 casualties, not counting the wounded and missing. Throughout this hell, Lynn lost his platoon leader, his squad leader, all of his platoon. All were seriously wounded. Garold Tidball he had shared a foxhole with the previous night, died in front of him. « Under this deluge of fire, I got pinned down with Garold, right behind a small parapet. I was scared and almost in panic, but I above all had this strong desire to survive. I realized that they had us zeroed in and I told Garold we had to get out of here. He told me that here or elsewhere, it was just the same. I moved out about fifty yards, without him. A shell landed right on the spot I had just vacated. The right side of his face was blown away, and he died instantly, only three or four hours into combat. Ironically, the previous night, Garold had been telling me over and over that he was not going to make it. »

Lynn Aas had a long and painful day, isolated and pinned down by machine gun fire. « When darkness set in, as I was moving through a field, the Germans opened up on me with machine gun fire from a hundred yards, for ever an hour. I was pinned on frozen ground, in the snow, hidden by a small knoll of ground. Thirty feet in front of me laid the lifeless body of Richard Miller, another of my comrades mortally hit behind me. I could see tracers flying a few inches over my shoulder and neck, but they never hit me. I remained unable to move for many hours, until the snow began to fall real hard. I then proceeded to crawl away. Even though I was a bad posture, I never considered surrendering. » Lynn would eventually rejoin his company on the next daya round 10.00, after struggling along in the snow to avoid the enemy. Cold and wet, he reached a foxhole occupied by two 327th glidermen of the 101st Airborne Division, who took care of him until first light. In his report, he delivered useful intelligence to his superior officers. That got him a Bronze Star Medal. After this first day in combat, Lynn’s squad record was bad : out of 13 men, only five were fit enough to fight. Many companies had similar records.

On the next day, frostbite victims added up to combat casualties, worsening D company’s record. From January 9th until 12th, in defensive position, 2/193GIR relieved the 327GIR in Champs and in the woods south of town, leading recon patrols, establishing outposts and taking prisoners. German artillery fell occasionally. The weather situation did not improve, except on January 12th in the afternoon, when the sky cleared up a bit, allowing Allied air support. Lynn went on patrol and on observation missions.

In the night of January 12-13, the Germans evacuated the area, and the 193GIR took up position in Front of Flamisoul and facing the wooden patch they could not seize on January 7th. At 08.15, they started moving up north, through Frenet, Givry and Gives, then turning north east towards Bertogne and Longchamps that they reached early in the afternoon. The two battalions set up position in the woods between Bertogne and Longchamps. They learnt that they were now attached to the 11th Armored Division to form two Task Forces for a pincer attack on a pocket of resistance in Compogne, about three kilometers to the east, along the Houffalize road. Lynn and the battalion ended up with Task Force Bell that moved up at 10.00 on January 15th, on the nothern edge of the road. Despite artillery and mortar fire, and the loss of a few tanks, Rastate and Compogne were taken around 16.00 hours. To the south, Task Force Stubbs, including 1/193GIR met growing enemy resistance and only seized its objectives the following morning. At night, both group lead aggressive patrols to the east.

On January 16th, the regiment moved out quickly and reached Cowan, about two and half kilometers south east of Houffalize, making room for the 194GIR. Around midnight on January 17th, the 193GIR was relieved by the 507PIR and sent to the rear for rest in Mabompré until January 21st in the morning. During that time, Divisionmoved up rapidly to the point that neither logistics nor food could keep up, men living on supplies taken from the enemy or scrounged in farms.

On January 21st, 193GIR caught up with division in the woods south west of Tavigny, despite heavy snow, ice, German roadblocks and mine fields. Pfc. Aas reached Limerlée on the next day in the afternoon and was about to enter the Grand Duchy of Luxemburg through Hautbellain, in hot pursuit of the remnants of the 9. And 130. Panzer Division as well as the 26. Infantrie Division trying to reach the Siegfried Line.

The attack on the village started on January 23rd at 08.30. By 14.00 hours, Lynn’s company was mopping up the village. They once again faced enemy artillery and stubbom resistance, but cleared the objective. Two hours later, patrols from his company were sent towards Huldange, to make preparations for the next day’s attack. They brought back prisoners and reported a mined road, and a boody trapped village, as well as two blown up bridges.

On January 24th, still under machine gun and artillery threats, 2/193GIR moved up towards the north east, along the Watermal and Huldange border line, secured a patch of woods and linking up with 1/513PIR coming from the north. All day long, they repulsed Germans leading delaying actions against the Americans. Bivouacking in the woods, the 193GIR was reinforced by the 194GIR.

To the outskirts of the Siegfried Line :

Thursday Janauary 25th stands as a milestone in the regiment’s history : on that day ends the Battle of the Bulge, and begins the Rhineland Campaign. 2/193GIR kept supporting the 194GIR before transferring by truck to Erpelange-les-Witz at 22.00 hours the next day, to relieve elements of the 26th Infantry Division and 317th Infantry Regiment, 80th Infantry Division. This short break allowed replacements to fit in, to clean up weapons and to look after materials. Arriving in Bockholz-les-Hosingen in the evening of January 27th, the battalion sent out patrols to Hosingen to look things over. The patrols found out that the 988. Volksgrenadier Regiment, 276. Infanterie Division had deserted the village, leaving boody traps. On the next day, 2/193GIR entered the village and conquered the high grounds in the north east and south east, while 1/193GIR remained in reserve close by. These were the premises of larger maneuvers aimed at pushing the Germans beyond their borders and the Siegfried Line.

On January 29th, at 14.00 hours, in knee deep snow, 2/193GIR started its attack and reached the river three hours later. However, the German resistance pushed the Americans back, helped by heavy artillery support. D Company once again suffered heavy casualties. In a defensive position until January 31st, Lynn was involved in night patrols and infiltration missions less than 600 yards from the Siegfried Line, to probe the German defenses. Some patrols even reached the river. Defensive position and outlook posts were established to observe the bunkers, machine gun nests and artillery positions, all bustling with activity. The regiment then faced the 5. Fallschirmjäger Division. Weather did not improve, with low temperatures and limited visibility. For an entire month, Lynn’s nerves were shattered because of continous mopping up missions. The Germans were everywhere. « Fighting a smart enemy was no easy task, but dealing with the severe weather conditions of thet winter 1944-45 subjected us to extreme test of physical and mental thoughness, way beyond all understanding. Only those with a strong will and good physical condition were able to survive. Thanks to luck and God, I made it alive. »

On the last day of January, trooper Aas arrived in Erpeldange-les-Wiltz where he rested until February 10th. Along with his comrades, he was billeted in barns and public buildings. For all of them, it was paradise. Since arriving in France five weeks earlier, he had only slept twice under a real roof. « The first time was in a Belgian barn next to a house, and the second time, I slept on the floor inside a building on low grounds during our advance. All night long, our 240mm guns were blasting away from behind our buildings. With each blast, mye ars were ringing. » During this time, men of the battalion helped clearing the streets from rubbles, and handled dangerous ammunitions. About this time, temperatures began to rise, melting snow and exposing dead bodies. From February 2nd till 4th, the men were dispatched through a resting area set inside the Saint-Josph school in Virton, Belgium, where over shoes were distributed, although kind of late, along with thick socks, spare gloves and clean clothes, following a warm shower. Following so many hardships, pain and fear, this interlude behind the lines were more than welcome for Lynn.

Pfc. Aas remembers the horrendous losses suffered by his company that winter. Dozens of soldiers were unaccounted for, either dead, wounded or missing or evacuated because of frostbites. His reinforced platoon for examples went into combat on January 7th with 55 men. A month later, only five men emerged unscathed, a mere 9% of the initial figure. Those five brothers in arms were Pfc. Lynn Aas and John Madoni Jr., Private William Simington, Willard Mincks and Richard Elzey. At the end of the battle, Headquarters company 2/193GIR, the largest of all companies, could only muster 81 men and officers out of a 180 men roster. The smallest company only had 9 men left ! The 193GIR suffered the highest casualty rate among American units during the Battle of the Bulge. At the beginning of January, General Patton estimated that the 17th Airborne Division would only be facing decimated and demoralized German units. Reality proved him wrong.

In combat, Lynn wore the standard olive drab uniform, with large cargo pockets on the pants, without ranks or insignia. Whenever possible, he would wear overshoes. Wool gloves with leather palms, one blanket, overcoat and long wool underwear were his only protections against the cold. He remembers getting new underwear once every two weeks while in France, Belgium and Luxemburg. « It was so cold that I would just put one layer over another, to the point that I would wear three layers of underwear under two pairs of wool pants. This number of layers became a problem once I got dysentery from eating too many frozen K rations. I was always going hungry. » Hygiene was nonexistent, as washing, teeth brushing and shaving were impossible. His personal weapons were an M-1 Garand rifle, bayonet and grenades.

Châlon-sur-Marne, a new era :

On february 6th 1945, the 17th Airborne Division’ staff was briefed about Operation Varsity, that aimed at establishning a bridgehead across the Rhine river in the early days of April. As a central figure in this operation, the division had to leave the Grand-Duchy of Luxemburg to make preparations. Therefore, the 193GIR reached Châlon-sur-Marne in France on January 11th at 19.30. Upon arrival, Lynn got involved in getting the billets ready, as nothing had been prepared. The camp was quite muddy because of lousy weather, although not as bad as previously experienced. Pfc Aas lived in a pyramidal tent. Life conditions were returning to normal, although far from peace time comfort. Moroever, Lynn took sick. « This is about the time when I developed a severe infection on my left cheek. It swelled and forced my eye to shut closed. My right eye also got in trouble and I had to be hospitalized. Sulfamids and penicillin did the trick and cured me. I also got rid of dysentery. » The heavy casualties suffered by the regiment in January lead to the disbandment of the unit on March 1st. Lynn subsequently was assigned to Able Company, 194GIR, still as a regular rifleman. More training, practice flights went on intensively during an entire month. The date of the operation was set forward due to the fast pace of ground troops.

Varsity was a Top Secret operation, but German intelligence services were alerted as early as the 10st of March. Anti-airborne units were rushed to the Wesel area, on the Rhine banks to welcome the 17th Airborne Division and its sister unit, the 6th British Airborne Division. On March 21st, Lynn boarded a truck, then a train, to get to A58 airfield located in Coulommiers, about 45 miles east of Paris. D-Day would be March 24th.

« Operation Varsity » combat in the heart of the Reich :

On March 24th 1945, Lynn Aas woke up at 04.30 in the morning. He had breakfast, geared up and boarded one of the thirteen CG-4A Waco gliders carrying his company as part of Serial A9. Take off for landing zone « S » LZ-S located north east of Wesel, Germany, was 07.30. A C-47 troop transport aircraft pulled his glider along with another one in double toe. After a relatively peaceful flight in perfect weather conditions, the glider was fired upon and damaged while crossing the Rhine River.

Around 10.36, in spite of bad visibility due to preparatory bombardment, explosions, smoke screens and fires, Lynn and his eleven comrades had rough landing. « My glider hit the ground in a field inside the given perimeter. Landing was rough. The glider slid on wet grass, went through some barbed wire fences and collided with another glider. The left wing was torn apart, just like the one from the other glider. That first obstacle did not stop us and we hit another glider, losing our right wing ! » The little group got out in a hurry and helped capture a little while later about fifty prisoners, before heading for the pre-planned combat positions. Most of 1/194GIR landed as planned around 10.30, west of the Issel River. Its mission was to take and secure that stream of water and capture its bridges. Enemy resistance slackened on LZ-S at 11.15 but fighting resumed all around. By noon, Regiment assembled 75% of the troops and three hours later, had the field definitely secured, altough sporadic sniper fire lasted until the next day. That evening, 1/194GIR had a firm grip on its positions west of the river, facing the German line of resistance on the other side.

During the day, as B company was in reserve behind the front line, Lynn’s A company spread along a 1.000 yards line along the Issel, from south to north, starting at the Bärenschleuse lock. C Company had some trouble reaching its objectives, ambushed by small German units dug in ditches and patches of woods to the north east, around the little hamlets of Grenzenlust and Vierwinden. South of LZ-S, 2/194GIR was spread all along the front line as planned along the Issel Canal, from Wesel to the lock. Generally speaking, the regiment was facing elements of the 84. Infanterie Division supported by many different scattered 20mm Flak units, as well as 88s and self-propelled gun « Stumgeschütz ».

On March 25th, after a memorable night lighted lika a 4th of July, laced with artillery and small arms fire, A/194GIR repulsed some skirmishes as it mopped up its surroundings. « Around 14.00 hours, I lost my friend John Madoni. He was killed by a well-aimed sniper bullet. He was one of the five comrades who had made it through the Ardennes. » By the and of the afternoon, once the situation had calmed down a bit around Lackhausen, Lynn’s platoon settled down in a patch of woods that offered some cover. Along his comrades, he dug in for protection, as German counter attacks were always possible. « Willard Minks and I were getting comfortable in our foxehole for the night when the Germans opened up with tree bursts. There was an explosion right above me and I got hit in the left arm by shrapnel. This was the end of my combat career. »

During that operation, Lynn Aas was wearing the standard olive drab uniform with large cargo pockets typical of airborne troops, with the American flag on the right sleeve. He wore long underwear, a wool sweater, wool gloves with leather palm, grenades and a first kit pack attached to his helmet net. His personal weapon was still the M-1 Garand and his personal equipment was made of a webbing, belt, musette bag, canteen, folding shovel and bayonet.

The end of an era :

On March 26th, an amphibious truck carried Lynn to the west bank of the Rhine, to a military tent hospital. Soon, a sanitary train took him to Belgium where on the next day, around 02.00 hours a surgeon removed the shrapnel in his arm. « Best part of the story was when I woke up : the first person I talked to was a beautiful Red Cross nurse. She gave me toilet articles and asked me a few questions to tell my folks. » Later on, Pfc Aas’ convalescence resembled a tour of Europe and America.

After being operated upon in Belgium on March 27th 1945, Lynn spent about six weeks in a military hospital in Paris, France, where medical personnel treated his wounds. Being able to walk and not considering him as physically disabled, Lynn took the opportunity to visit the city, with his arm in a sling. He was in the French capital when he learnt of the passing of President Franklin Roosevelt on April 24th. Soon after the capitulation of all German armies on May 8th, Lynn left Paris and moved to Ramsbury airfield in the United Kingdom. Next step of his voyage was at Bristol on May 21st when he boarded on a hospital ship which, after an eight days crossing, arrived in New York harbor.

The Army then decided to send him to the west coast ; to another hospital in Spokane, Washington. This transfer was probably meant to get him closer to his relatives. During his stay, he was able to go on leave to visit his family. His parents had left the country life and settled in Valley City, North Dakota, as his dad was no longer fit to run the property and the farm. On August 15th, as he was visiting his family, he heard with great joy of the total surrender of the Japanese army. From Spokane, Pfc Aas eventually ended at Hot Springs, Arkansas, where he watched over a Japanese war prisoners camp.

He by then had enough point for a discharge, comforted by the fact his dad was at this time in need for medical care. Rather than granted him a leave for personal reason, the Army granted him an honorable discharge on November 1st 1945 at the Hot Springs Separation Center, six weeks after the deactivation of the 17th Airborne Division, on September 16th at Camp Myles Standish.

Because of his wound and convalescence, Lynn did not follow his unit in Germany. From March 26th on, his battalion began to move ever faster. Every day, German resistance was getting weaker and weaker and hundreds of prisoners were taken in by passed villages such as Lembeck, Wulfen, Dorsten, Dülmen, Haltern and Nottuln. On April 2nd, 194GIR took Muenster with the help of the 513PIR. After veering to the south west and the Rühr industrial basin, the regiment fought its last battle, near Arnsberg on April 16th. Should he have made it that far. Pfc Aas would have stayed in Duisburg with his comrades. He would not take part of the eight weeks from mid-June till mid-August spent in the garrison city of Luneville, France, before the big ship home.

A successful life :

Back to civilian life, Lynn Aas went back to school at the University of North Dakota, and received a Bachelor in Commerce in 1948, and became a law doctor a year later. He then worked as a special agent for the Internal Revenue Service, a government run agency that collects taxes and enforces the fiscal laws. He lived in Minneapolis, Minnesota where he met Beverly Stockstad, a qualified nurse from Sioux Falls, South Dakota, whom he married in 1952. A short time later, the young couple moved to Fargo, North Dakota. In 1960, Lynn moved to Minot, North Dakota where he handled businesses for the Medical Art Clinic. Thanks to his Masters in Law, he got involved in the North Dakota legislature in 1967, 1969, 1987 and 1989, becoming a member of the Constitutional Convention of the State in 1972. He retired from the clinic in 1985 and has ever since been involved with various organizations such as the Minot Kiwanis Club and the Minot Chamber of Commerce he presided in 1975 and 1976. He remained a member of the board of directors of United Way, a company he ran in 1964. In terms of education, Lynn favored the development of the Minot State University, initiating among others a program for medical care. This benevolent involvement got him two awards in 1983 and 1985.

The couple had four sons, David, Paul, Daniel and Joseph. In 1999, Lynn went to Europe on a trip organized by the Veterans Association of the 17th Airborne Division. He had the opportunity to visit places he had discovered fifty-four year earlier. He attended many 17th Airborne Division veterans’ reunions. Beverly died on March 31st 2003. Today, Lynn still lives in Minot, about fourtyfive miles from his native town, and sixty miles from the Canadian border. He likes to hang around Otter tail lake, Minnesota, and spend some quality time with his four sons and eight grandchildren. Golf is his favorite sport.

Private First Class Aa sis recipient of the following medals and awards : Glider Badge, Combat Infantryman’s Badge, Purple Heart Medal, Bronze Star Medal, Good Conduct Medal, American Theater Medal, European African Middle Eastern Theater of Operation Medal with one Bronze Arrowhead and three Bronze Campaign Stars, WWII Victory Medal. Lynn served in the army during eighteen months and twenty-two days overseas, including sixteen dayx at sea. Once back in the US, he remained another five months and three days until his discharge. His overall service time in the army amounts to two years and eight months. He participated in the Ardennes, Rhineland and Central Europe Campaigns. He also displays the Expert Rifleman Badges for both the M-1 and the BAR. He received a Purple Heart Medal for his wound sustained in combat on March 25th in Germany. He recived the Bronze Star Medal for bravery in action. The official citation for this award states that after the January 7th fighting’s near Mande-Saint-Etienne, he successfully escaped the German lines and brought back important information to his unit.

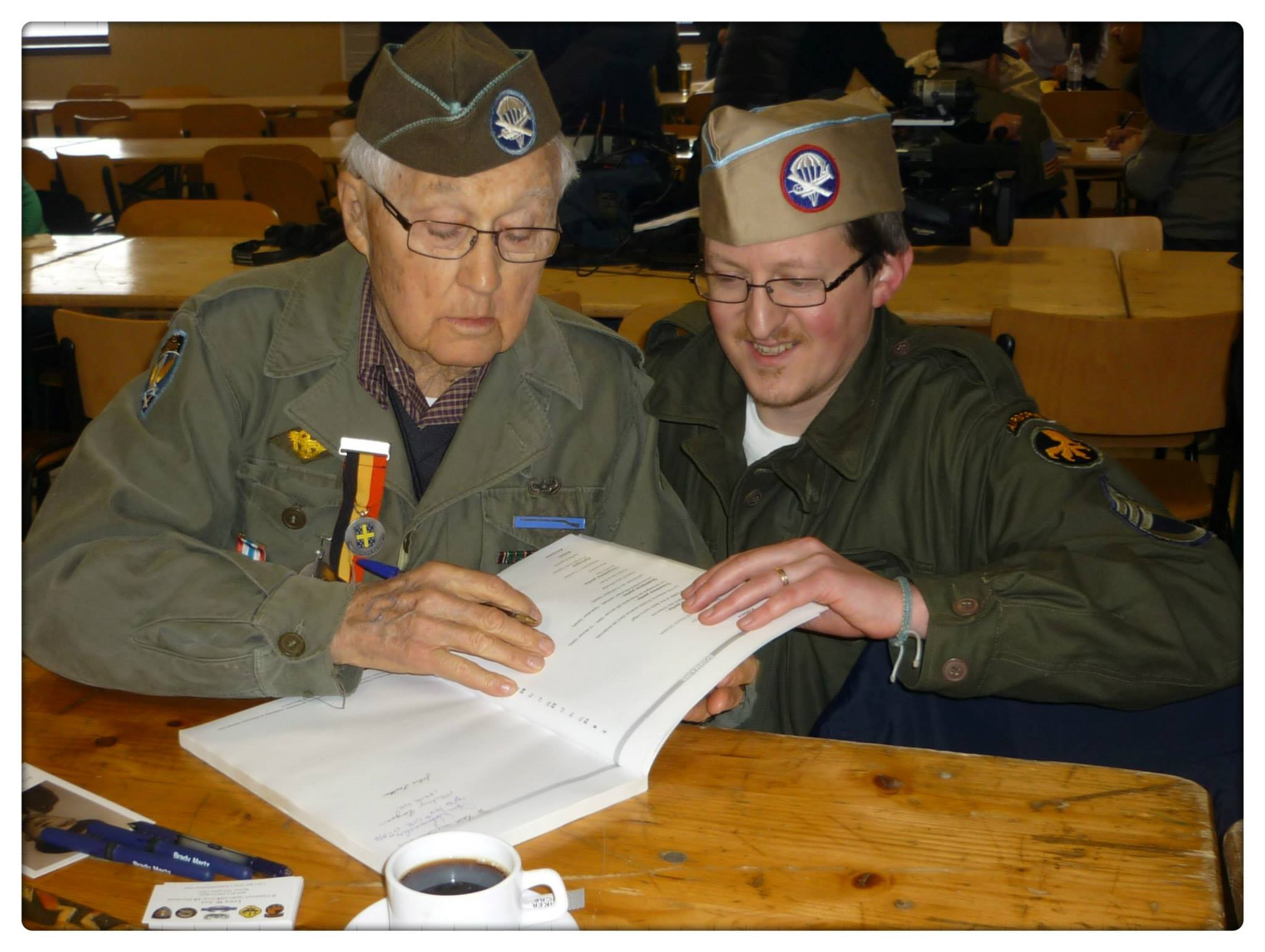

Lynn Aas lors de son grand retour en Belgique le 24 mars 2015.